By: Randy Tucker

Cafferal and Helmer made a beeline for Ten Sleep to alert the Big Horn County sheriff in Basin and a posse was quickly sworn in.

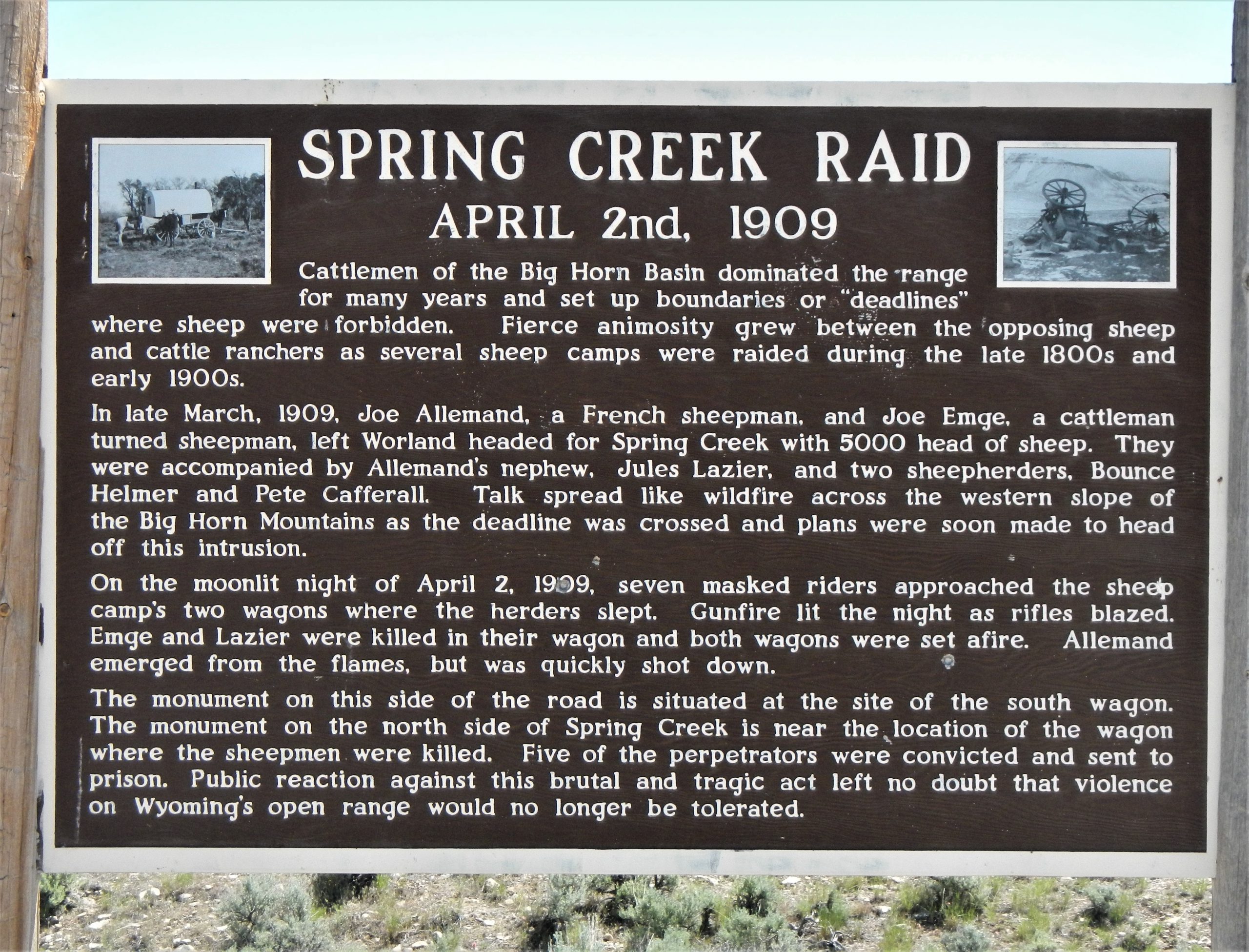

The posse arrived at the crime scene on April 3. The sheriff and his deputized posse found the bodies of Allemand, Emge, and Lazier, the two burned wagons, a pair of sheepdogs, killed by the cattlemen, and about 25 dead sheep.

The herd was scattered over several square miles. Without men and sheepdogs to keep them in groups, they wandered off in small groups to search for grass.

Identifying the killers was a challenge on many fronts. No one had ever been brought to trial, much less convicted of killing sheepherders or destroying their property in Wyoming before, but the Wyoming Wool Growers Association had enough of the violence against their members. They put a $5,000 bounty for information leading to the conviction of the killers, and the National Wool Growers Association added another $2,000 with an additional $1,000 reward offered from Big Horn County. An extra $500 in reward money was offered in a half-hearted effort by the State of Wyoming.

The five men convicted of the brutal killing of three sheepherders at Spring Creek. Photo credit: Wyoming State Archives

In 2023 dollars, that $8,500 total from 1909 is worth $280,000 today, a substantial incentive for someone to talk.

Cafferal and Helmer had a good idea of who the attackers were, but since the killers were all wearing masks, they couldn’t be identified in a lineup by the survivors.

The reward wasn’t necessary, loose talk by Brink and Dixon in the bars of Basin and Greybull sealed the case. They didn’t fear prosecution since every killer of sheepmen in the state prior to their criminal act went unpunished.

One of their friends, William “Billy” Goodrich, contacted Big Horn County Sheriff Felix Alston and identified Brink and Dixon and all the other five as the attackers.

Alston let Brink and Dixon know that it was to their benefit to get the rest of the criminals to surrender themselves before a grand jury convened a few weeks later in Basin.

Keyes and Farris surrendered soon after to Alston.

The gravity of the crime, combined with the tension between the Wyoming Wool Growers and the Wyoming Stock Growers Associations, and national attention directed towards the tiny town of Basin, had Wyoming Governor Bryant B. Brooks involved.

Brooks, with a team of attorneys from the Wyoming Attorney General’s Office, met with Goodrich, Keyes, and Farris in Sheridan.

Sheridan was on the east side of the Big Horn Mountains, opposite Basin to the west side of the 11,000-foot range and far enough away to avoid attention as the governor met with the two culprits. Keyes and Farris turned state’s rights and testified against their fellow ranchers in exchange for a pardon from Brooks and safe passage out of the state. As guilty, but pardoned participants, they weren’t eligible for the reward money.

Back in Basin, warrants were issued for Saban, Brink, Eaton, Dixon, and Alexander. They were arrested without resistance on May 3.

A few days before the five were arrested, another attacker, previously unknown, couldn’t handle the pressure of impending arrest and shot himself. Billy Garrison may or may not have been involved in the raid but was one of the men at the bar that Brink and Dixon bragged to. He couldn’t handle the pressure of testifying against his friends and chose to end his life instead.

The county coroner ruled Garrison’s death a suicide, but for decades after, many Big Horn County ranchers believed he was killed by the attackers to prevent him from testifying in the trial that began in county court in Basin, one of the smallest county seats in Wyoming, along with Lusk and Sundance.

All seven men on trial either pled guilty or confessed outright to the crime. Keyes and Farris as first-hand witnesses, and Goodrich who heard the bragging of Brink and Dixon, all implicated Brink as the man responsible for the three murders.

Farris had his accusation of Brink recorded verbatim in the court record. “I heard Brink shout: ‘Show a light and come out,’” Farris said. “A man appeared at the front of the wagon. ‘Hands up!’ cried Brink. The man’s hands were in the air as he came towards us. Then Brink said: ‘This is a hell of time o’ night to come up with your hands in the air!’ There was a shot. Who fired it? Herbert Brink.”

The compelling was enough to convict Brink and he was sentenced to be executed at the Wyoming State Penitentiary in Rawlins, but it was later reduced to life imprisonment.

Saban and Alexander received 25-year sentences after pleading guilty to second-degree murder.

Dixon and Eaton were convicted of arson for burning the two wagons after dousing them with kerosene and given three-year sentences.

The convicted criminals boarded a train from Basin south to Rawlins on November 20, 1909. Crowds gathered at the train station to give the convicted criminals food, blankets, and other gifts.

Farris, Keyes, and Goodrich left without fanfare, escorted to the Wyoming border by a Big Horn County deputy sheriff.

Eaton died in prison, Dixon served out his sentence, and was paroled in 1912. Saban escaped from the penitentiary in 1913 and was never found again. Brink and Alexander served five years and were paroled in 1914. Reducing the two men’s sentences from life and 25 years to just five years by Governor Joseph Carey, a well-known cattleman, was indicative of the power of the Wyoming Stockgrowers Association and their ability to influence political decisions.

Wyoming State Penitentiary at Rawlins in the early 20th century. Photo credit: Wyoming State Archives

The convictions ended the persecution of sheep ranchers by cattlemen.

“It is significant of the beginning of a new era, of a period where lawlessness in any form will be no more tolerated in Wyoming than in the more densely settled communities of the east,” William Metz, one of the prosecuting attorneys in the case, said.

Isolated incidents between individuals over grazing rights continue to the present day, but felonies are rare.