By: Randy Tucker

It’s not something you see in the Hollywood version of Old West cattle range battles, but Emge used his friend’s phone to call his wife and let her know they’d be back home in a couple of days.

Rural phones outnumbered the ones in America’s cities in those days, but there weren’t many single lines to rural locations. Phones in those days were party lines, meaning a single line shared by many people. Up to 30 homes in some locales shared the same line. Each home had an individual ring pattern of long and short rings. Your home could be two longs, and two shorts, or maybe the reverse, or any other combination of the four. Every home heard that ring pattern and answered only if the rings indicated a call for their home.

But, and this is the “but” that tipped off the cattlemen who attacked the Allemand-Emge party, anyone could pick up their receiver and listen to the conversation. When Emge called his wife, the rings for his house were heard all along the shared party line.

One of the cattlemen, who shared the line, monitored calls to Emge’s sheep ranch and listened in quietly as he told his wife of their anticipated arrival. In the subsequent court trial, it was determined this is how the ambush site was determined.

What isn’t known is if the phone line was a standard single copper line or one of the “barbed wire” systems that ranchers and farmers used from the early 1890s to around 1920 to extend the range of expensive telephone lines. Barbed wire fences were used to carry phone signals in many areas of the vast American West.

Dinner went a little long, well into the night, and since it was a dark night, they decided to bed the sheep down nearby. They were still several miles from the deadline.

At the Keyes Ranch, a couple of miles away, a group of eight cattlemen gathered to attack the sheep party.

The leader of the group was George Saban, owner of the Bay State Cattle Company. He was a prominent member of the Wyoming Stockgrowers Association and one of the largest cattle producers in the state. He always had a propensity for vigilantism as expressed six years before when he led a lynch mob that killed two prisoners and a deputy sheriff at the Big Horn County Courthouse in Basin.

It’s not clear whether Saban was involved in another attack in 1905 when a group of 10 masked men attacked sheepherder Louis Gantz in Shell Canyon, east of Greybull, and clubbed approximately 4,000 of Gantz’s 7,000 head of sheep to death. Gantz survived the attack but lost $40,000 in sheep which brought about $10 a head in those days. No one was ever tried for the attack.

Joining Saban were Milton Alexander, Tommy Dixon, Charles Farris, Ed Easton, Albert Keyes, and Herbert Brink, along with one and possibly three more cattlemen who escaped indictment.

The five sheepmen had settled down for a night’s rest in the two wagons, with only a dying campfire illuminating the moonless night.

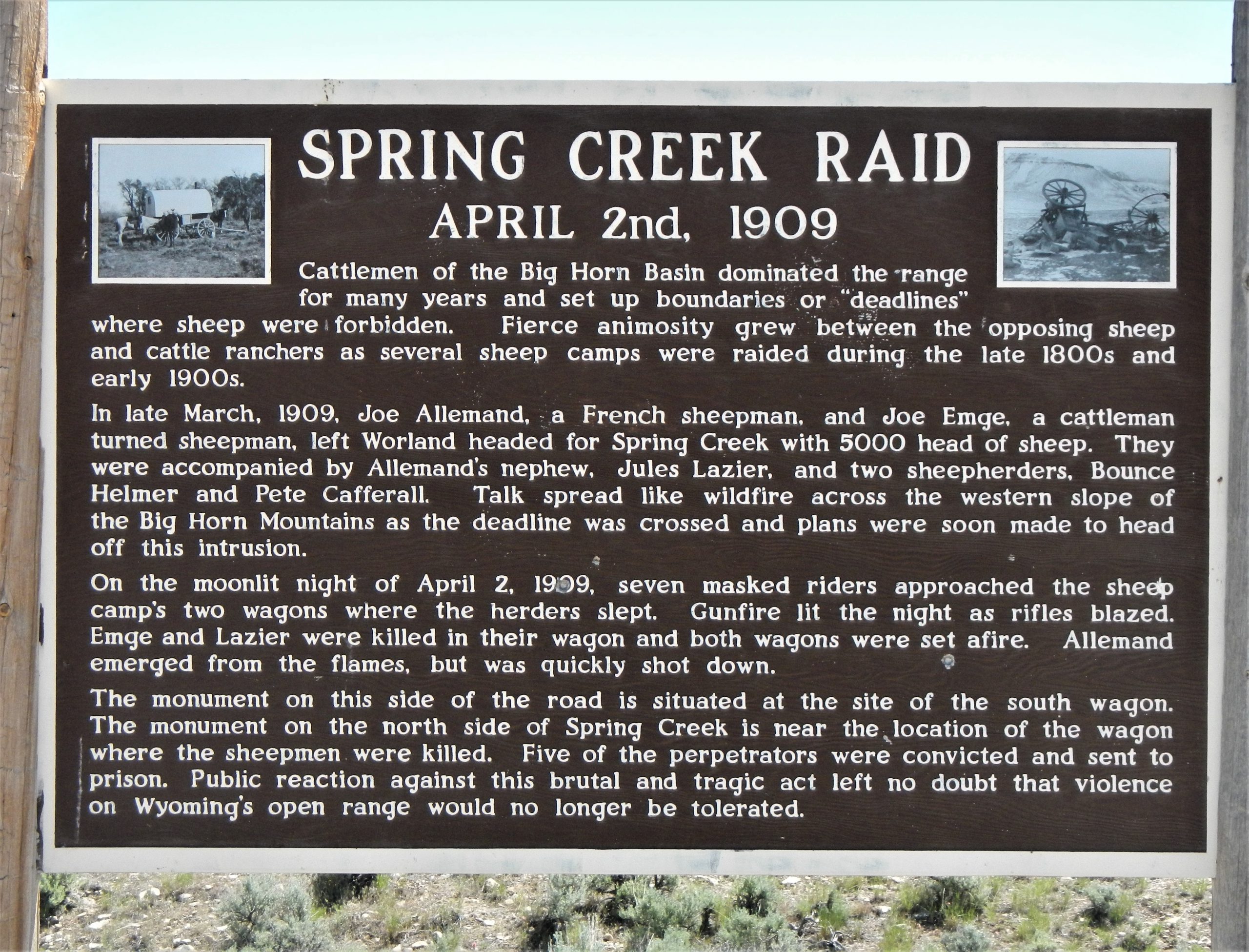

Cattle vigilantes attack a sheep camp. Photo credit: Harpers Weekly

Saban’s party split into two groups and approached the wagons in the darkness. They came within pistol range of the wagons and Saban called out into the night for Allemand to surrender. When Allemand opened the door to his wagon, they opened fire, hitting him in the head, neck, and chest. He fell from the wagon dead.

The opening shots awakened another pair of cattle ranchers camped about a quarter mile away. Porter Lamb and Fred Greet approached the scene and were eyewitnesses to the ensuing violence.

They could clearly see the muzzle flashes of the attacker’s rifles and heard the shots a few seconds later as the sound carried to the ridge they were descending.

After a couple of minutes, the raiders stopped firing, and Lamb and Greet watched as the two wagons went up in flames. They heard the sound of horses rapidly leaving the scene and then traveled the short distance to witness the carnage at sunrise the next day.

Allemand was dead, flat on his back with bullet holes in his neck and side. Amid the smoking ruins that had been the sheep wagons just an hour before were the charred bodies of Emge and Lazier. At first glance, Lamb and Greet couldn’t tell they had been killed by rifle fire before their bodies were burned in the wagons. An autopsy later verified the cause of death as large caliber bullets fired at close range.

Helmer and Cafferal, the two surviving herders, had a harrowing story to tell. They’d been captured at gunpoint before the shooting started, had their hands tied, and were tied to nearby trees.

They were spared, according to speculation, because Helmer’s father was believed to be one of the unidentified cattlemen in the attacking party that was never officially identified.

Helmer and Cafferal claimed they had untied the ropes and escaped, but later testimony at the trial by the defendants said they had set the duo free. The truth is unknown but leans toward escape rather than being freed since defense attorneys tried to play up the compassion of the men who supposedly set Helmer and Cafferal free.