By: Warren Gray

Copyright © 2022

“Now, therefore, take your weapons…and go

out to the field and take me some venison.

And make me savory meat…that I may eat.”

— Genesis 27:3-4.

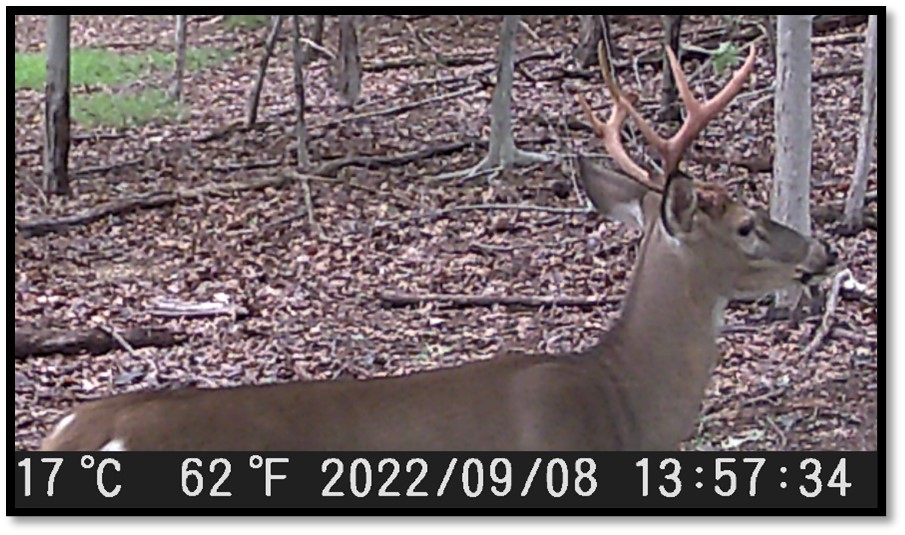

It was 7:15 AM on Monday, September 12, 2022, in the deep forest near Pleasantville, Maryland, precisely at official sunrise. However, the sun’s golden, morning light was still obscured by the nearby, 1,476-foot massif of Elk Ridge, or Elk Mountain, known during the Civil War as Maryland Heights. But 7:15 was when it happened. I’d been hunting whitetail deer for the past three days, and into the morning, with my Barnett/Wild game Innovations XB370 crossbow. Seated in an open tree stand 18 feet (20 feet at the seat) above the forest floor, I was clad in an Army-surplus, MultiCam-pattern, camouflaged uniform, searching for the healthy, eight-point buck that I’d seen on my trail camera a few days previously.

The morning had been uneventful. I was bored after sitting still for over an hour in the densely wooded terrain, facing north, with a 63-foot-deep ravine (measured by Google Earth) 72 yards to my left, with a creek at the bottom, and a rising hill to my right, extending only 350 yards uphill, to Hoffmaster Road, at the base of Elk Ridge. The ridge was named for the hardy herds of majestic elk that once roamed its wooded slopes in the mid-1700s, until they were hunted to extinction in the region not long afterward.

Barnett/Wildgame Innovations XB370 camo crossbow. Photo credit: Wildgame Innovations.

The 18-foot tree stand in the forest, with author in ATV/bike helmet. Photo credits: Adam Gray.

Since the opening of whitetail archery season on September 9th, I’d hunted seven times in this same tree stand on a neighbor’s property, totaling 13 hours thus far. I’d seen nothing but does and fawns, with a single, six-point buck far out of crossbow range. I shifted uncomfortably in my seat as I detected movement to my left, in brush that rose from the ravine below. Suddenly, I was stunned by the rapid appearance of a small, bachelor herd of three sizeable bucks, including a six-pointer and two more whose antler tips I was unable to count in the dim lighting beneath the heavy canopy of trees.

I immediately slipped the fairly noisy safety mechanism of my crossbow from “Safe” to “Fire” before they approached closely enough to hear it. With my heart pounding from excitement, trying to remain totally motionless as they crested the rise from below onto the rough, ATV trail at my feet, where I’d unloaded a zip-lock bag of shelled corn only an hour before (it’s legal to bait deer in Maryland). One of the three continued onward uphill, to my right while the six-pointer and the third buck cautiously doubled back toward the corn. They were 70 yards away, still outside the effective range of my crossbow.

My first crossbow kill, an eight-point buck, September 17, 2020. Photo by author.

The weapon had fallen over only two days previously. I had just sighted it in, putting an arrow straight through a one-inch bullseye at 25 yards. So, I’d positioned the patch of corn exactly that same distance from my tree-stand for a perfect, accurate shot. The two bucks warily held back under the leafy trees, however, approaching the corn in a circumspect manner, initially pretending to be disinterested. However, one of them eventually broke cover and stepped out to sample the small pile of yellow corn.

I could see that his antlers were oddly shaped and uneven (“wonky,” as one of my neighbors had described), but I still could not count all his points in the dim lighting of the green forest. He was very clearly an antlered buck, however, the largest of the three by far in body weight alone. I took careful aim just behind his front legs, midway up the body, and squeezed the trigger. My Barnett Headhunter 20-inch, carbon bolt took off at 370 feet per second as I had a clear, broadside view of my target at the precise, desired range, with a razor-sharp, 100-grain, Allen Stryke Impact broadhead screwed onto the tip (I also use G5 Outdoors Montec, solid-steel broadheads on some arrows.)

There was almost no noise upon impact with the buck’s left side, just a dull, muted thump, and he and the other two deer, all still within 80 yards from my position, flashed away toward the north, running at an estimated 30 miles per hour toward the deeper cover and concealment of the lush, summer forest. I slowly and carefully descended from the tall, 18-foot platform. Walking forward to the corn, I retrieved my bloody arrow from nearby, confirming that I’d made a solid hit on his heart/lung region.

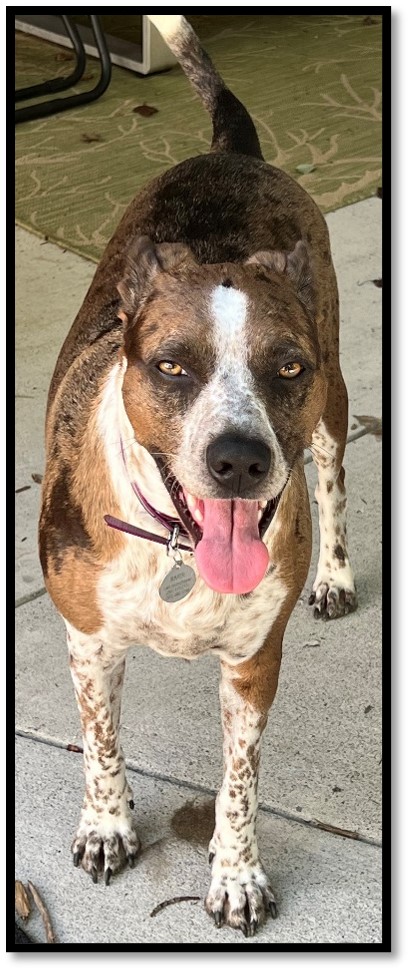

Tracking him on foot in the dimly illuminated woods, proved to be a futile effort, so I had to awaken my neighbor, Vince Strosnider. Vince was a certified firearms instructor and NRA Life Member upon whose land I was hunting. I asked him to bring one of his dogs to help track down the elusive buck. Less than a year ago, we’d had great success together in tracking a wounded, six-point buck through the forest (See my previous, Gunpowder Magazine article, “Dogs and Deer: ‘A Four-Legged Tracking Machine’” from October 24, 2021), but his older dog, Winter, had since died. This time he brought another dog, River, a three-year-old, female, Catahoula Leopard Dog mix, originating in Louisiana, out to sniff the bloody arrow and follow the deer’s scent.

River, the Catahoula Leopard Dog. Photo by Vince Strosnider.

All went well for the first 250 yards, as River rapidly acquired the buck’s blood trail, heading northbound, and clearly enjoying stalking an animal in the wild. We followed her on foot, until we reached a noticeable, circular spot of blood on dry leaves, where the deer had obviously stopped for a few seconds, still bleeding. Sadly, we lost the blood trail, and mistakenly assumed that the buck had continued northward in a straight line. River became less and less certain of its direction of travel. We crossed the creek to the opposite side for about 150 yards but had no luck and came back to the eastern slope of the ravine again, still searching the thick brush without result.

After about 15 more minutes of fruitless tracking, I decided to start all over again at the tree stand, and follow the blood trail once more, since it was the only positive evidence of the buck’s dramatic exit from the target zone. After 250 yards, I came upon the same circular patch of blood where the deer had stopped momentarily. I was puzzled and began fanning out in a measured grid from that one bloody patch. Soon, I detected a drop of fresh blood six feet farther west, so I headed 90 degrees left, downhill into the ravine, just above a dense, leafy thicket shielded by some fallen logs to the north and east.

Cautiously descending the slippery, leaf-covered hillside, I looked to my left, deep into the shady thicket, and saw the prostrate form of my large buck, lying dead in the forest, with his odd, five-pointed antlers angled uphill.

“Hey, Vince, I have a deer body over here!” I called out to my neighbor, who was beside the creek about 100 yards farther north, still searching with his dog, River.

Suffice it to say that it took Vince, my wife, and me the next hour, assisted by our four-wheel-drive, Honda Rancher 450 ATV, to drag that substantial, heavy beast 30 yards uphill with a rope around the antlers, and a further 40 yards behind the ATV, to reach the trail where the animal could be field-dressed safely. The extraordinary exertion in the 75-degree, 97-percent humidity, summer morning caused me to break out in a dripping sweat. My condition is shown in the photo at the top of this article, posing with my fresh kill for a moment before extracting my custom-made, Özekes Brothers (Turkish-made, since 1890) #110 carbon-steel, hunting knife (with rosewood grips) to remove the internal organs before meat processing. He was definitely the largest and heaviest deer that I’ve ever taken, despite the modest, crooked, five-point rack atop his head.

After removing about 20+ pounds of organs onto the forest floor, this fine buck later weighed in at 138.6 pounds fully field-dressed, so he was about a solid 160 pounds in the wild, in a region where most eight-point bucks weigh in at about 120 pounds. While the antlers were not that impressive, his overall size certainly was, since I only outweighed him by a mere 12 pounds at the time, as the photo shows quite well.

Coincidentally, my well-used, XB370 crossbow was on its last legs, with one of the high-pressure, bow limbs cracking and delaminating after a few years. So, for the sake of safety, I had to acquire a brand-new crossbow within the next few days from a nearby (62 miles) Pennsylvania outfitter whose selection was considerably depleted because prime, crossbow season was already well underway in many states. The new crossbow cost a few dollars more, and was slightly more powerful, at 210 pounds of draw weight and 405 feet per second arrow speed.

The elusive, eight-point, whitetail buck that got away. Trail-cam photo by author.

The two accompanying bucks escaped unscathed, including a visually confirmed, six-pointer and the handsome, eight-pointer captured for posterity by my trail camera (above) four days previously. Since we’re only permitted one archery-season buck harvest in my state, I’ll have to wait five weeks for the brief, muzzleloader season to open in order to hunt bucks again. In the meantime, there’ll be plenty of fresh venison in the basement freezer for the coming year, and we enjoyed delicious, spicy, deer-loin fajitas for lunch yesterday and today (from last year’s six-point, crossbow buck) as I write this article.

Crossbow hunting isn’t for everyone, since it doesn’t drop the deer as quickly as a rifle or muzzleloader, but it has its place. Extending the local, archery hunting season out to nearly five months, it’s a worthwhile endeavor. In the Eastern states, especially where there is regional or political sensitivity to using firearms for hunting, crossbow hunted deer may be harvested quietly, even in built-up, suburban areas. For my region, crossbow hunting is especially useful early in the archery season, because the deer have not yet become accustomed to the sight and scent of hunters in the woods. They travel in roving, bachelor herds of prime bucks, so in these circumstances, crossbow hunting is certainly swift, silent, and deadly.

* * *

Warren Gray is a retired, U.S. Air Force intelligence officer with experience in joint special operations and counterterrorism, and is an NRA member. He served in Europe and the Middle East, earned Air Force and Navy parachutist wings, four college degrees, and was a distinguished graduate of the Air Force Intelligence Operations Specialist Course, and the USAF Combat Targeting School. He currently a published author, historian, and deer hunter. You may visit his web site at: warrengray54.vistaprintdigital.com.