By: Warren Gray

Copyright © 2022

“Today, we are officially resuming operations at the U.S. Embassy

in Kyiv. The Ukrainian people, with our security assistance, have

defended their homeland in the face of Russia’s unconscionable

invasion, and, as a result, the Stars and Stripes are flying over the

Embassy once again. We stand proudly with, and continue to

support, the government and people of Ukraine as they defend

their country from the Kremlin’s brutal war of aggression.”

— Secretary of State Antony Blinken, May 18, 2022.

The Embassy of the United States of America in Kyiv, Ukraine, located at #4 Aircraft Designer Igor Sikorsky (Ukrainian-American engineer, born in Kyiv in 1889) Street, was constructed in 2012, at a cost of $247 million. It occupies 11.1 acres (300 yards long by 150 yards wide) near the western outskirts of the capital city. The address was previously known as Tankova (“Tank”) Street, but the Kyiv City Council changed the name, upon a specific request from the American embassy.

Since the Hunter Biden Scandal of 2019, in which President Trump felt that his efforts to investigate Hunter Biden and Burisma Holdings’ corruption in Ukraine were being undermined by U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine Marie L. Yovanovitch, an Obama appointee, there was no official U.S. ambassador to the nation. Chargée d’affaires Kristina Kvien served as acting ambassador, instead, from January 2020 until very recently. On May 18, 2022, Bridget Ann Brink, a career foreign service officer, was officially appointed as the new U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine, having previously served as U.S. Ambassador to Slovakia. She speaks English, French, Georgian, Russian, and Serbian.

The U.S. Embassy in Kyiv has normally been staffed by 181 Americans and more than 560 Ukrainians. However, since the Russo-Ukrainian Crisis of 2021 to 2022, the embassy staff temporarily relocated to Lviv in the west, only 35 miles from the Polish border, and then into Poland itself as tensions escalated a few days before the Russian invasion on February 24, 2022.

All 165 American military, advisory personnel were withdrawn from Ukraine before hostilities commenced along with the U.S. Marine Corps embassy security staff. This was done to prevent the appearance of any U.S. military activity within the country as the Russian Federation massed it forces at the border. The permanent U.S. Embassy compound was left secured by Diplomatic Security Service (DSS) agents, who are armed, civilian employees of the U.S. State Department. Each of them has a minimum of a bachelor’s degree and has to graduate from an intensive 29-week training course.

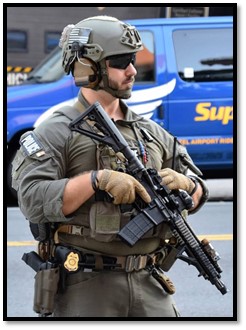

The embassy was formally reopened on Wednesday, May 18, 2022, with a small, flag-raising ceremony attended by 11 embassy employees, a few photographers, and two armed plainclothes DSS agents keeping watch. These agents normally wear civilian clothes, but they also have green assault uniforms marked with either “Police” or “Federal Agent” tags, available for certain operations.

Their primary armament consists of the Glock-19M pistol (the same, standard-issue handgun as the FBI, since 2015) in 9mm, Glock-26 in 9mm for concealment or off-duty usage, Colt M4A1 carbine, and Remington 870 shotgun. Additional weapons include the H&K MP5 submachine gun, Colt Mk. 18 Mod. 0 carbine (frequently photographed), M203 40mm grenade launcher, M249 Minimi light machine gun in 5.56mm, and M240G medium machine gun in 7.62mm NATO. Even the M2HB heavy machine gun in .50 BMG is sometimes employed.

DSS mobile security agent with Mk. 18 carbine and Glock-19M pistol in New York City, 2019. Photo credit: Reddit/U.S. State Department.

Interestingly, the U.S. Embassy in Kyiv is directly across the street from the NATO Liaison Office (NLO) in Ukraine, although the country is not a NATO-member nation. During the few months that the U.S. Embassy in Kyiv was inactive, the compound was constantly secured by DSS agents. It is encircled by nearly 1,000 yards of gray, concrete wall, topped by a tall white slatted-steel fence line.

The wartime activities of the U.S. Embassy in Ukraine remain classified, but one can certainly speculate on them with some degree of accuracy. This author had more than 12 years of experience as a full-time U.S. Air Force intelligence specialist and intelligence officer (plus nine years in other officer duties); graduated from USAF Combat Survival School; served for two years as an intelligence paratrooper in a joint special operations unit; entered and exited the U.S. Embassy compound in Bucharest, Romania, almost every weekday for six months (and occasionally coordinated with the Regional Security Officer or RSO); and very briefly worked at the State Department headquarters in Washington, DC after military retirement. So, I can perhaps make an educated guess as to recent, possible, embassy activities.

With DSS agents protecting the compound, it was, in all likelihood, not evacuated completely. A small key staff was probably left behind consisting of CIA intelligence analysts, perhaps a few National Security Agency (NSA) signals intelligence experts and National Geospatial Intelligence Agency (NGA) satellite imagery experts, and a handful of CIA Special Operations Group (SOG) paramilitary field operatives. (See my Gunpowder Magazine article on “Desert Tigers: Guns of the CIA Special Operations Group” from January 26, 2021.)

CIA SOG paramilitary operative. Photo credit: Pinterest.

A medical staff of one or two doctors and nurses would also be essential, in case of any war-related injuries to embassy personnel. The roving SOG operatives, likely armed with HK416A5 carbines and Glock-19 pistols, would require some type of light, nimble ground transportation for reconnaissance patrols around the bombed-out city during the Russian assaults. The Polaris Defense MRZR Alpha 2 or Alpha 4 turbodiesel all-terrain vehicle, as favored by U.S. Special Forces, would be perfect in this role. Also, the Ukrainian e-bike company Eleek makes very light (only 140 pounds), nearly-silent, olive-green, Eleek Atom Military electric dirt-bike motorcycles ($5,220 each) for battlefield usage (see eleek.com.ua/en), already in Ukrainian Army service.

These brave men would also be highly likely to coordinate with MI6 paramilitary operatives from the small, nondescript British Embassy in Kyiv, at #9 Desyatynna Street, less than a half-mile from the main port area of the broad Dnipro River and four miles southeast of the U.S. Embassy. It was also officially closed until late April, but probably had a tiny intelligence staff on hand. After all, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson has been by far the most active and aggressive of world leaders in supporting the Ukrainian war effort. He was the first to visit Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy in Kyiv, on April 9, 2022, just over one week after a British-supplied shoulder-fired Starstreak missile shot down a Russian Mi-28N Havoc-B attack helicopter in combat.

The Department of State Air Wing (DoSAW) also possesses several types of helicopters that would be extremely useful for embassy support in wartime, as there are a few areas within the compound where they could possibly land (the main courtyard, the parking garage roof, and the large grassy pad in front of the flagpole, for example.) GoogleEarth satellite imagery helps to readily identify these areas. Available aircraft include the UH-1H Huey II transport (light gray or camouflaged); the HH-60L Black Hawk medevac chopper (Sikorsky S-70A design, dark blue over light gray), either armed or unarmed; and the hand-launched short-range RQ-11B Raven-B aerial drone for local reconnaissance.

We know for certain that sensitive U.S. intelligence information passed on to the Ukrainian armed forces has resulted in the combat deaths of 12 to 15 Russian generals, so some type of on-scene intelligence staff seems quite necessary.

In addition, Bell Helicopters very recently (February 15, 2022) introduced their brand-new Bell 407M (military) helicopter gunship, an armed version of the latest Bell 407GXi variant, advertised as “the world’s most cost-effective, multi-role helicopter.” It has .50-caliber GAU-19/B Gatling guns and 70mm advanced laser-guided missiles. It’s conceivable that the CIA may have one operating from nearby Vasyl’kiv Air Base, home of Ukrainian 40th Tactical Aviation Brigade and the mythical “Ghost of Kyiv” MiG-29 fighter pilot. It’s located just 13 miles south of the city to provide close air support for their CIA SOG teams on the ground who are advising and assisting Ukrainian forces.

As a readily available alternative to a newly built aircraft, the U.S. Army’s ultra-secret Aviation Technology Office (ATO) special operations unit at Felker Army Airfield on Fort Eustis, Virginia, already operates at least five dark-gray Bell 407GX unarmed transport helicopters, which have recently been openly photographed during military exercises.

At least one or more of them could be swiftly and easily converted into Bell 407M gunships, with the GXi engine upgrade for six-percent more horsepower (862 HP), an MX-15Di FLIR sensor installed, and the necessary CFD international ordnance-mounting system (OMS), and appropriate weapons. Since ATO has already coordinated with the agency on various covert combat operations, the simplicity of “loaning” a modified Bell 407M to the CIA for special operations use in Ukraine seems like a foregone conclusion.

These are just some of the possible, wartime activities that a wise, responsible, forward-thinking, and well-informed U.S. administration might quietly conduct from a skeleton-staffed U.S. Embassy near the front lines of battle, although this may be giving the Biden administration far too much credit. They may have done only some of these things, or more than likely, none of the above.

As of May 23, 2022, President Biden is seriously considering securing the embassy with U.S. special operations forces (SOF) in coordination with the Pentagon. This is the very same president who hastily withdrew all 165 U.S. troops (65 Special Forces advisors and 100+ Florida National Guard advisors near Kyiv) from Ukraine on training missions just four months ago, making it much easier for Russian forces to attack without worrying about U.S. military casualties.

The current concern is that Russian missiles or artillery could inadvertently target the embassy compound, which is legally sovereign U.S. soil under international law. If so, the combat situation could dramatically escalate, even though Russia is fully aware that the U.S. uses military personnel (Marines) to guard its embassies around the world, so any such presence should not necessarily be viewed as escalatory.

However, introducing any U.S. military forces into Ukraine at this point could certainly lead to a Russian perception of escalation, since Biden has been consistently adamant that American ground troops will not fight in Ukraine. If U.S. SOF troops do re-enter the country in the near future, then we must be able to provide a rapid, exit strategy to extract them and the embassy staff from the embattled country rapidly if the situation worsens, and the only current, viable options are slow ground transportation via road or rail to the border.

In any event, this deployment requires a presidential decision, and it would mean Joe Biden completely reversing his recent decision to bring all Green Berets and other U.S. soldiers out of Ukraine. But, stranger things have happened in the past. Time will tell.

* * *

Warren Gray is a retired, U.S. Air Force intelligence officer with experience in joint special operations and counterterrorism. He served in Europe (including Eastern Europe) and the Middle East, earned Air Force and Navy parachutist wings, four college degrees, and was a distinguished graduate of the Air Force Intelligence Operations Specialist Course, and the USAF Combat Targeting School. He is currently a published author, historian, and hunter. You may visit his web site at: warrengray54.vistaprintdigital.com.