By: Warren Gray

Copyright © 2020

“Survival can be summed up in three words, ‘Never give up.’ That’s the heart of it, really. Just keep trying.”

— Edward M. “Bear” Grylls.

It can happen to anyone, anywhere, in the blink of an eye. You’re on a road trip to your vacation cabin, or to a rural B&B, or a family gathering for the holidays, and you take a turn a little too fast, or hit a patch of black ice, or a deer suddenly lunges out in front of you, and you skid off the road and hit a tree.

You and your passengers are unharmed, but you’re in the middle of nowhere, at least 10 miles from the nearest town, there’s no cell-phone signal to call for help, no GPS signal, and no passing traffic to flag down. Maybe it’s even late fall or winter, and it’s cold outside. You’re stuck, possibly for a day or two, until help can arrive. What do you do now?

As a graduate of the U.S. Air Force Combat Survival School at Fairchild Air Force Base in Spokane, Washington, and as a former intelligence specialist who taught refresher, survival skills to American fighter pilots (in case of being shot down) in Germany for four years, I can offer some specific and useful recommendations for basic, road-trip, survival gear that might help you through an unfortunate incident in the woods. As with most things, survival gear clearly falls into the category of, ‘Better to have it and not need it, than to need it and not have it.’”

When I attended Survival School, it was a cold February, with three to seven feet of snow on the ground in the Colville National Forest, at an average of twenty-four hundred feet in elevation, so I also learned quite a bit about winter survival, as an added benefit. On a humorous note, I once removed my Air Force-issued snowshoes to evade through an area where the trees were very close together, and instantly dropped through more than six feet of snow to the hard ground below, with the top of my head barely visible to my assigned, evasion partner, a female helicopter pilot. We both had a good laugh over that, and I slowly and carefully climbed back out, hand-over-hand up a narrow, tree trunk, and put the snowshoes on again. Lesson learned: the snow is often much softer and deeper than you realize!

Since the COVID-19 virus pandemic has put a long-term hold on international travel, my wife and I have been taking short, local, overnight trips instead, often into rural areas to see the attractions and stay at nice, historic B&Bs in uncrowded areas. We don’t need to pack a lot of bulky luggage, so there’s plenty of room in the trunk for some emergency survival gear, just in case the worst-possible scenario happens.

First, we have an insulated, Coleman sleeping bag rolled up in the trunk during cold weather, just large enough to keep the two of us warm all night, if necessary. Second, and most important, is our automobile survival kit. This is basically just a Rubbermaid Roughneck container, filled with two first-aid kits (Johnson & Johnson, or similar, about $16 to $18 each, from Walmart), one Glock folding shovel ($48, and they call it an “entrenching tool”), one heavy-duty, towing strap with hooks, two highway flares, one flashlight with spare batteries, one squeegee/windshield wiper, one Air Force Survival Manual, and a separate, auto survival kit with jumper cables, fuel siphon, tow rope, poncho, electrical tape, zip ties, and a mylar “space blanket.” Add a well-equipped, tool kit (about 15 to 20 pounds of all types of basic, hand tools), and that’s our survival gear just for the vehicle.

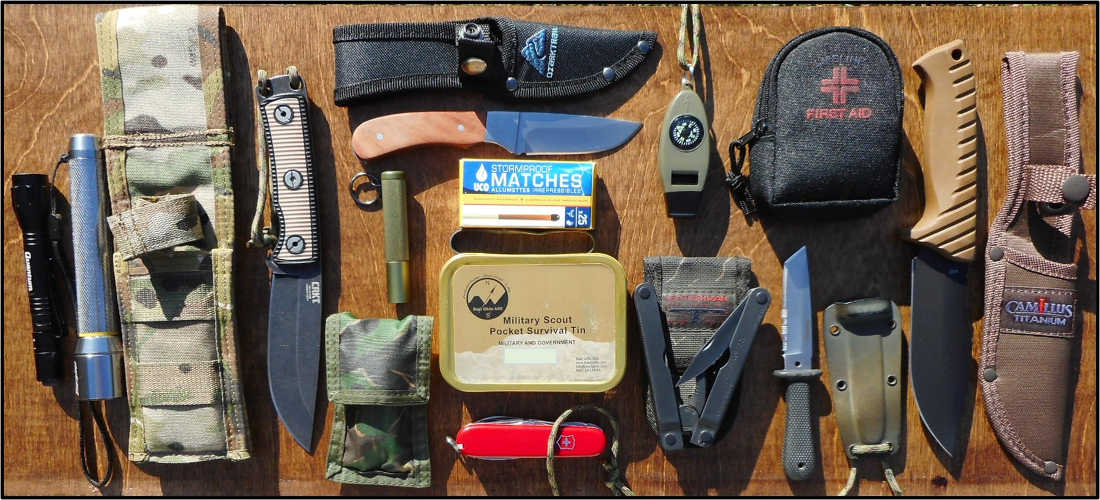

Now we come to the personal survival items that you might want to carry in your backpack or luggage, in addition to the car kit. Obviously, a cell phone with built-in, GPS-navigation feature is highly desired, if it works, and if you can get a signal at all. Some of the items that fighter pilots find in their survival kits are just as useful for you and me today: a GPS unit, small, first-aid kit, compass, flares, signal whistle, matches in a waterproof container, survival knife, pocket knife, Gerber or Leatherman multi-tool, small canteen, bottles of water, magnesium fire-starter, penlight flashlight, leather gloves, wool socks, and sleeping bag.

If you happen to be carrying a concealed handgun, legally, that could also be helpful under certain circumstances, particularly if your vehicle breakdown occurs in black bear territory, for self-defense or scaring the bears away. It’s really best to sleep inside your car and avoid the bears altogether, though.

I used to own a camouflaged, Charter Arms (now made by Henry Repeating Arms) AR-7 Explorer survival rifle in .22 LR, and a Springfield Armory M6 Scout (no longer in production, although Chiappa still makes a similar model) survival rifle in .22 Hornet and .410, but seldom actually carried them on road trips. They’re nice to have in a serious, survival situation, however, because a .22 rifle can harvest small game to eat, such as birds or rabbits. There are other fine rifles from Chiappa, Marlin, Ruger, and Savage that work just as well, and a .22 LR pistol or revolver could also serve you quite nicely, but this isn’t really the type of survival gear that we’re likely to pack just for an overnight trip or other, very short trip.

My Democrat-controlled, anti-Second Amendment state has highly-restrictive guns laws, and self-defense with a firearm is actually illegalhere, where merely wearing, carrying, or even transporting a handgun is also a crime (“prohibited by law” is the official wording by our State Police.) However, our largest city, run by a Democratic mayor, currently leads the entire nation in homicide and violent crime, so the liberal laws clearly do not make us safe. As a result, I don’t often carry a gun here (there are certain exceptions) for defense against two-legged predators, using pepper spray and a Smith and Wesson, double-edged dagger instead, as an absolute minimum.

Building a fire may become essential, for warmth as well as morale, so you’ll definitely need some matches, a hefty, survival knife for cutting wood, and possibly a wire saw for cutting larger branches. I’ll usually bring one very rugged, high-quality, survival knife, such as my CRKT/Ruger Powder-Keg ($100, but discontinued), together with a decent, lower-cost knife, such as a Camillus Titanium (from Walmart), so we always have two available, and even Ozark Trail (Chinese-made) produces some good, usable knives for just $10. I also own a superb, Cold Steel SRK (Survival-Rescue Knife), but I don’t carry it that often, and the Glock FM81 survival knife is another rugged and affordable choice.

Some type of small, portable, survival kit in a tin container is highly recommended, and these are available from Adventure Survival Equipment (ASE) at www.adventuresurvivalequipment.com or www.bestglide.com. I carry their Military Scout Pocket Survival Tin (#SK1340M), which is only 4.5 inches long, 3.3 inches wide, and 1.2 inches deep, in my overnight bag, but it contains a huge variety of vital, survival items for $34. They have many other survival kits and tins available, however, ranging in price from $16 to $306, depending upon the complexity desired. ASE provides kits for the U.S. Army, Air Force, Marine Corps, Civil Air Patrol, FBI, DEA, State Department, NASA, and even the Boy Scouts. I usually rubber-band a pack of 25 windproof, waterproof, stormproof matches from UCO Gear (Utility, Comfort, and Originality) at www.ucogear.com to my survival tin, just to be on the safe side, so I always have them.

ASE also sells a wide variety of survivalknives, including the Air Force Survival Knife, Ka-Bar Marine Corps Knives, Swiss Army Knives, and inexpensive ($16), Morakniv Swedish Survival Knives, as well as top-quality, ESEE-4 survival knives ($190.)

A small, personal, first-aid kit in my overnight bag is essential at all times, plus a top-quality, Victorinox Swiss Army Knife, and sometimes a Leatherman multi-tool. Every now and then, I’ll also add my Cold Steel ParaEdge neck knife with 2.8-inch blade, just to have another small, high-quality knife on-hand. I sometimes bring a small, inexpensive, Coughlan’s Four-Function Whistle ($8) that combines a signal whistle, tiny compass, magnifying glass (for helping to start fires on sunny days; remember burning ants when you were a kid?), and thermometer into one handy unit with a neck cord.

Packing two flashlights (and spare batteries for both) is the best option, so you always have a backup. I carry a SureFire G2X Pro for serious work, and a smaller, Eveready Energizer, Quantum, or Cabela’s penlight for my bedside. There’s an old, survivalist saying that, “There’s no such thing as too many flashlights, or too many knives.” When I was an Air Force major, one of my sergeants routinely carried sevenknives. I didn’t ask to see them all, but I believed him.

Today, I typically carry at least three knives at all times, including two with 1.8-inch blades (one is a Gerber AUS-6 Ridge Knife), and one with a three-inch blade. They’re tools, not weapons, and I use them every day to cut strings, open boxes, open food containers, and for a variety of other very ordinary purposes. Whenever I’m driving, my keyring also holds a Victorinox mini-Swiss Army Knife, with a tiny, 1.45-inch blade, so that technically makes fourknives on my person at all times. My sergeant also wore a boot knife and neck knife for military purposes, so his seven total knives suddenly doesn’t seem so extreme, after all. Go figure!

My wife normally packs one modest-sized, insulated cooler, with a frozen, gallon jug of ice inside, to cool about five bottles of water and five cans of Coke Zero, which we gradually consume during each mini-trip, but they’re also normally available in case of a breakdown. You can only live about three or four days without water, and if you’re stuck in a remote area for a few days, you’ll need something to drink.

With the exception of the bulkier, car survival items (sleeping bag, survival kit, and tool kit), none of these personal, survival items take up much space in my overnight backpack, so it’s not an inconvenience at all. I rarely, if ever, need them, but they’re always there, within quick, easy reach, in case of an emergency, and I did use the first-aid belt kit once when my oldest son and I reached the top of a mountain, and he cut his finger with a knife while opening a food pouch for lunch. The alcohol pad and Band-Aid were quite helpful. My trusty, Leatherman tool once repaired a loose doorknob in my military office in Romania one year. And my Swiss Army Knives in standard and keyring sizes have seen a lot of very practical use over the years. You just never know when one of these small, survival items may be useful.

Obviously, we didn’t acquire all of this survival gear at once. It took at least 30 years to obtain this much, a little at a time, so don’t think that you need it all right now. The best place to start is a good-quality, Swiss Army Knife, waterproof matches, and a decent-sized, first-aid kit, all of which you should be able to purchase for well under $90. Then, start adding more gear a little at a time, until you feel comfortable with your inventory of emergency survival supplies.

Practice starting a small campfire until you can consistently do it with just one match. It takes a little preparation, starting with tiny, wood shavings or similar tinder, and then adding progressively-larger sticks on top as you strike the match, until you can place log pieces on top, and get them to burn. Practice in a fireplace, wood stove, fire pit, or in a safe place in your back yard. Your first, actual, survival experience in the deep woods should notbe where you also learn, the hard way, to start a good fire.

We once stayed at a nice, cozy cabin in a state park during the winter ski season, with snow on the ground. The park staff supplied plenty of larger firewood, but almost no starter materials, and the sticks on the ground were all wet, so we learned to sometimes bring our own tinder material, dry sticks, and a few dry log pieces to get a good fire going, as well as some decent, wooden matches. If you’re able to plan ahead like this, an empty, 12-pack, Coca-Cola box stuffed with two wadded, paper bags from the grocery store makes a great, slow, fire-starter, with about a half-dozen dry sticks on top, and then two dry log pieces on top of that. It works like a charm!

Remember also that there’s no need to overdo the survival preparations and gear. Carry just enough that you feel fairly safe and comfortable in case of an unexpected breakdown in a remote area, without using excessive trunk space. Your vacation luggage still has top priority, but any survival gear that you can pack will give you peace of mind, and could possibly even save your life under harsh circumstances. It’s a lot like buying a self-defense pistol. You have to ask yourself, “How much is my life worth to me?” A few hundred dollars in vital, survival gear, even when acquired very slowly over time, may someday pay you back in untold benefits if the worst case ever happens.

Warren Gray is a retired, U.S. Air Force intelligence officer with experience in joint special operations and counterterrorism. He served in Europe and the Middle East, earned Air Force and Navy parachutist wings, and four college degrees, including a Master of Aeronautical Science degree, and was a distinguished graduate of the Air Force Intelligence Operations Specialist Course, and the USAF Combat Targeting School. He is currently a published author and historian. You may visit his web site at: warrengray54.webs.com.