By: Randy Tucker

It was right out of a 1950s Western, but this was no movie. A hail of gunfire, a flaming wagon, and the death of three sheepherders marked the end of the undeclared range war between cattlemen and sheepmen on the high plains in the darkness of the April 2, 1909, night.

Even the names sound like something from Hollywood, the event was known as the Spring Creek Raid, it occurred in No Wood Canyon just a few miles south of the historic Wyoming mountain town of Ten Sleep.

Tensions were on the rise between sheepherders and cattle ranchers on the open range of public land in Wyoming.

Contrary to the beliefs of the cattlemen, no one had a greater claim on the land than anyone else. The grazing went to the man who had the agreement with the federal government to graze his livestock, no matter the species.

Wyoming cattlemen, at least the wealthier ones, were still peeved at the results of the Johnson County War fought 18 years before on the other side of the Big Horn Mountains near present-day Buffalo. In that historic affair, small cattlemen were attacked by professional killers, hired by the Wyoming Stockgrowers Association in Cheyenne.

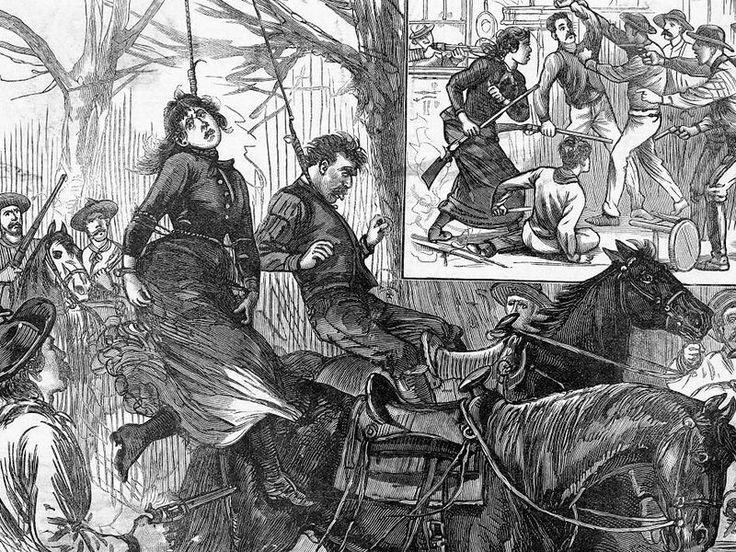

The war began when Ella Watson, better known as “Cattle Kate,” and her husband Jim Averill were captured and lynched by the hired guns. They were hanged from a cottonwood tree for allegedly rustling cattle. The war ended with the Stockgrowers Association losing stature and backing off their attempted takeover of smaller ranchers. None of the hired guns were ever sentenced, but big ranching took a hit in public opinion when the dust settled.

An artist rendering of the lynching of Ella Watson “Cattle Kate” and James Averill. Photo by smithsonianmag.com

That hit evidently didn’t extend to sheep ranching.

Cattlemen have always claimed sheep ruin the range by digging up grass and other edible plants by the roots. Sheepmen, in response, claim that cattle ruin waterholes by wallowing in the mud, polluting water and making it unusable for livestock. As usual, the truth was somewhere between these two extremes.

What isn’t up for debate is what happened when sheepherder Joe Allemand moved 5,000 head of sheep onto a leased section of public land south of Ten Sleep.

Spring Creek was designated as a boundary between cattle and sheep grazing in that portion of Big Horn County, extending south through present-day Washakie County and into Northern Fremont County. Sheep were to stay on the east side of the creek, and cattle in the west.

The informal agreement was reached in 1908 between the sheep growers and cattle growers associations but the sheepmen ignored the boundary, a line the two groups referred to as a deadline, and dead is what happened to one of the offending groups of sheepherders.

Joe Allemand and his partner Joseph Emge took a herd of 5,000 to 10,000 sheep, along with hired hands Jules Lazier, Charles Helmer, and Allemand’s nephew Pierre Cafferal across Spring Creek to the cattlemen’s section of the range south of Ten Sleep in March of 1909.

Allemand was regarded as a reasonable man who followed the unwritten guidelines established to keep the peace between the cattle and sheep growers, but Emge was a hot head, a man not afraid to challenge authority and one that was always willing to fight.

Emge was well-armed with an ample supply of ammunition and made his intentions known well in advance of the sheep drive. Both men knew what they were up against and had a deputy sheriff lead them to the grazing area to prevent potential violence from the cattlemen.

The herd was split along the Spring Creek deadline. They had two sheep wagons, and about a dozen dogs that they separated to maintain the two camps, the one legal camp to the east (according to the cattlemen) and the rogue camp on the west side of the creek.

Various stories attribute the split camp to a challenge by Emge to the cattlemen, but more likely there was not enough early grass for a herd of that size to graze on the east alone. The snow was just off the range and packing that many sheep into one area would fulfill the prejudice of the cattlemen by destroying grazing in the area. That’s a much more likely explanation for splitting the herd and violating the agreement than simple aggression.

Whatever the rationale, word spread among the cattlemen that there were sheep on “their” range and they were not happy.

On the trip out at the end of the month, the deputy declined to help them on their return. Emge didn’t mind since he had over a thousand rounds of ammunition, and a pair of rifles packed into his sheep wagon.

They took their time on the trip back home. On their leisurely return, they let the herd graze the trail and stopped at the home of a couple of friends to have dinner, a dinner that led to unexpected results.