By: Warren Gray

Copyright © 2022

“The unrealistic notion that this plane should be a ‘people’s fighter,’ in which the Hitler Youth, after a short training regimen…could fly for the defense of Germany, displayed the unbalanced fanaticism of those days.”

— Ernst Heinkel, aircraft designer and manufacturer, 1945.

By mid-1944, constant bombing by the U.S. Air Force during the day and the Royal Air Force at night had a devastating effect upon Nazi Germany, with the German Luftwaffe (Air Force), in particular, in a serious state of disarray. There were fuel shortages, logistics problems, maintanace issues, and a severe loss of experienced, veteran pilots. Casualties could not be replaced quickly enough, even with abbreviated training programs. The Luftwaffe decided to offset the Allied, numerical advantage with a technological advantage in the form of jet fighters, in particular the Messerschmitt Me 262A-1a Schwalbe (“Swallow”), which was faster than the best American and British fighters, and carried four hard-hitting, short-range, 30mm MK 108 cannon for blasting bombers from the skies.

Within the Luftwaffe high command, two advocacy groups emerged, one led by Lieutenant General Adolf Galland, a noted, fighter ace with 96 confirmed kills to his credit already, pressing for increased production of the Me 262, and the other group led by Reichsmarshall Hermann Göring, the head of the Luftwaffe, and Armaments Minister Albert Speer, seeking a new, jet fighter that was simple and inexpensive to produce, and could be flown by virtually anyone, with minimal training. Ultimately, Göring and Speer won the debate, and thus was born the concept of the Volksjäger, or “People’s Fighter.”

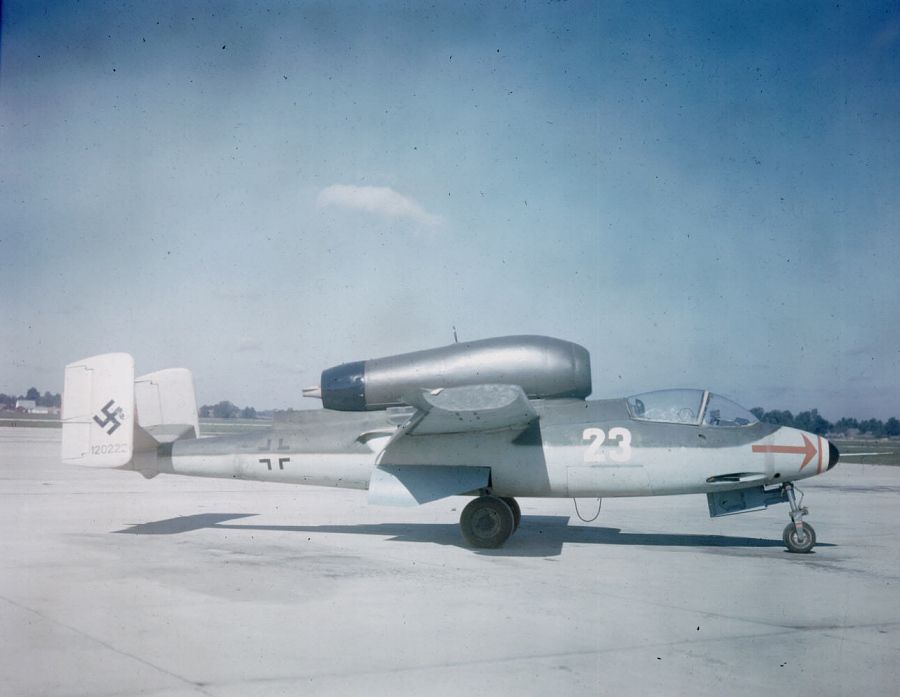

The requirement for an “emergency, lightweight fighter” was issued on September 10, 1944, just three months and four days after the massive, Normandy Invasion by the Allies in France. Ernst Heinkel’s radical design won the contract competition, originally named the He 500, but German officials trying to hide the project from Allied intelligence sources gave it the odd designation “8-162,” so Heinkel changed its official name to the He 162A Spatz (“Sparrow”), sometimes mistakenly referred to as the Salamander, which was actually the code name for its wooden production components.

The Heinkel factory in Vienna, Austria, at that time part of “Greater Germany,” assembled the new aircraft from parts constructed in various, underground facilities, using semi-skilled labor. Fully one-third of the weight of the new, jet fighter was comprised primarily of plywood, for the wings, fuselage, landing-gear doors, and nose cone. Heinkel had the first prototype completed and flown in just 74 days, by December 6, 1944.

Adolf Hitler was placing great faith in his series of technologically-advanced, Wunderwaffen, or “Wonder Weapons,” including the Me 262Aand He 162A jet fighters, the Ar 234B-2 Blitz jet bomber, the Me 163B-1a Kometrocket fighter, the V-1 “Vengeance Weapon” flying bomb, and the V-2 “Vengeance Weapon 2” ballistic missile program, to offset the Allied onslaught. Heinkel’s design was considered “sporty-looking,” and quite futuristic, with a sleek, streamlined fuselage, mounting a BMW 109-003E-2 turbojet engine on top, with a maximum thrust of 1,760 pounds, and an empty weight of only 4,000 pounds (about as much as my family SUV with two people aboard), which enabled an astounding, top speed of 562 miles per hour, making it the very fastest fighter of the war!

The original specification for armament called for two chunky, short-barreled, 30mm MK 108 cannon in the lower fuselage, with only 50 rounds of ammunition per gun, and these were, in fact, installed in the initial, He 162A-1 variant, but during testing, these anti-bomber guns proved too heavy, and the recoil was too excessive for the nose structure to handle. In addition, production of the 30mm cannon was halted due to Allied bombing, and the Soviets capturing the production factories. So, the limited production run of the A-1 version was stopped.

The He 162A-2 Spatz was the primary, operational variant, with its armament changed to twin 20x82mm MG 151/20 cannon with 120 rounds per gun. These smaller-caliber weapons were lighter in weight, generated less recoil, and permitted much more ammunition to be carried, with an advanced, Revi 16B/G reflector gunsight installed. There was a proposal to add two dozen R4M Orkan (“Hurricane”) 55mm air-to-air rockets beneath the wings, as were successfully mounted on the Me 262A-1b jet fighter in actual combat, but this bold idea never came to fruition.

The aircraft incorporated several advanced design features, including the BMW jet engine, retracting, tricycle landing gear (using the main gear assemblies from the existing, Messerschmitt Bf 109K fighter), and it was only the second operational fighter (after the He 219A Uhu, or “Owl” night fighter) to use an ejection seat. The plywood wings featured downward-angled (55-degee anhedral), duralumin (aluminum-alloy) wingtips, or winglets, for stability, and upward-canting, (14-degree dihedral) tail surfaces, with twin rudders, to clear the jet exhaust.

The greatest problem came from the poor-quality, wood glue used in the wooden airframe components, which was highly acidic, and tended to disintegrate the wooden parts that it was supposed to bond together. In fact, the first prototype was lost on December 10, 1944, when defective glue caused the right aileron to separate from the wing, and the plane to rolled over at low altitude (330 feet) and crashed, killing the test pilot.

During this period, over 200 test flights were undertaken, with more than 30 prototypes built, but the He 162A proved to be very complex and difficult, even dangerous, to fly, so the concept of young, swiftly-trained, Hitler Youth pilots was quickly abandoned. Production was supposed to begin on January 1, 1945, with 1,000 fighters produced per month, but this was always an overly-ambitious, unrealistic goal, which was never achieved. By the end of the war, only 116 fully-assembled aircraft had been delivered, with 200 more completed but still awaiting flight-testing, and a further 600 in various stages of production. Ultimately, however, only about 13 examples survived the war unscathed.

Most of the problems associated with the new fighter were the result of being prematurely rushed into production, not because of any inherent, design flaws. But, because of this hurried production, even before all of the prototypes were completed and tested, the He 162A had the worst safety record of all early, jet aircraft. The radical Spatz actually inflicted more casualties upon German pilots than the Allies. Of the 65 factory pilots assigned to He 162s, only five survived until the end of the war. None were lost to combat! The other 60 men all died during test flights or training crashes.

Due to the extreme shortage of qualified pilots, only two fighter units, I./JG 1 and II./JG 1 of Fighter Wing 1 at Leck, near the Danish border in the far north, managed to convert to the He 162A-2, with 58 aircraft supplied by late March 1945, and 25 more on the way, with orders to defend Berlin from Allied bombers coming from over the North Sea.

Despite its developmental problems, though, many veteran, Luftwaffe pilots called it a first-class, combat aircraft,” and British Royal Navy test pilot Eric “Winkle” Brown stated after the war that it had “the lightest and most effective, aerodynamically-balanced controls” that he had ever experienced, and was a very stable gun platform. But it still wasn’t ready for operational service until April 19, 1945.

Meanwhile, the Allies went after the Luftwaffe’s existing, Me 262A Schwalbe jet fighters with a vengeance. At 11:59 AM on Tuesday, April 10, 1945, the U.S. Army Air Forces began bombing the Me 262 air bases at Osnabruck, Wittstock, Oranienburg, Gardelegen, Dannefeld, Kitzingen, Neuberg, München-Riem, and numerous other bases for six straight hours on “Mission 341,” involving more than 1,300 American bombers and their P-51DMustang escort fighters. All 60 operational, Me 262 jet fighters were launched in response, attacking as many bombers as possible.

The official, U.S. losses for the day were 19 bombers (including 10 shot down by Me 262 jets, the highest, single-day loss to jet fighters in the entire war) and eight Mustangs, but the Germans fared much worse, losing 311 aircraft destroyed in the air, including 31 Me 262s (more than half of the remaining fleet), and 237 damaged. It would become known in history books as “The Great Jet Massacre.”

But the single, most-significant loss wasn’t shot down, after all. Captain Franz Schall, age 26, a winner of the prestigious Knight’s Cross, with 133 confirmed kills to his credit, including an unprecedented 16 (10 P-51 Mustangs and six heavy bombers) while flying the Me 262, making him the top-scoring, jet ace of all time (until 1953), belonged to JG 7 (Fighter Wing 7) at Brandenburg-Briest Air Base, 32 miles west of Berlin. After shooting down an American P-51D Mustang as his final kill, Schall attempted an emergency landing at Parchim, but his Me 262A-1b fighter, still armed with unexpended, R4Mair-to-air rockets beneath the wings, rolled into a bomb crater on the airfield, flipped over onto its back, and exploded. He was killed instantly.

The Great Jet Massacre was the final blow to the Me 262A jet fighter program, essentially terminating all remaining production and distribution, and emphasizing the utter futility of the Luftwaffe’s efforts to defend the Reich in the face of Allied air dominance.

By mid-April 1945, He 162As were operating from Leck and Rostock Air Bases, in the far north. On April 19th, near Rostock, a Heinkel He 162A-2 flown by Sergeant Günther Kirchner shot down a British fighter plane, unofficially scoring the first aerial kill for the new Spatz aircraft, and the Royal Air Force pilot parachuted to safety, but then, Kirchner himself was shot down by a British Hawker Tempest fighter, flown by Flight Officer Geoffrey Walkington, over Husum while he was on final approach to land, and ejected successfully, but his parachute failed to open, and he was killed. Later that same day, an American P-47D Thunderbolt fighter shot down another He 162 shortly after takeoff.

The very next day, April 20, 1945, Adolf Hitler’s 56th birthday, was the Luftwaffe unit’s first official, operational, combat mission, when they were assigned to attack a British-held airfield in northern Germany, but they were intercepted enroute by a group of Royal Air Force (RAF) Hawker Tempest fighters. One He 162 was shot down, but the pilot, Lieutenant Rudolf Schmitt, ejected and survived without injuries. Schmitt later claimed to have shot down a British fighter, but war records show that it was downed by German antiaircraft fire from the ground, instead. Two more ejections on April 21st and 24th were unsuccessful, the second when the aircraft’s canopy failed to detach.

Fighter Wing 1 (JG 1) lost a total of 13 fighters (10 in combat and three to mechanical failures) and nine pilots, but only three of the 13 He 162As were actually shot down. The rest were due to accidents. At least two pilots crashed while attempting dead-stick landings after running out of fuel. On April 30, 1945, Corporal Rechenbach shot down a British aircraft, and on May 4, 1945, Rudolf Schmitt made the only official, 100-percent-confirmed kill by an He 162A, shooting down a Hawker Tempest flown by Flight Officer M. Austin, who parachuted safely and was taken prisoner.

The He 162A-2 unit at Leck received orders to halt all further actions on May 5, 1945, and begin destroying their aircraft, but then the order was then confusingly recalled, so not all fighters were destroyed. On May 6th, the very next day, British forces seized the airfield, and recovered at least 11 intact, Spatz jet fighters for testing and evaluation later by the U.S., Britain, France, and the Soviet Union, who also acquired two airworthy examples of their own.

Overall, the He 162A Spatz jet fighter was an exceptional, elegant, and very innovative design, literally decades ahead of its time, which could have been a great, success story if developed properly, at an unhurried pace. Thankfully for the Allies, it was only fully operational for 16 days near the end of the war, for hardly long enough to make a lasting impression. Yet, it retains an honored place in world history as only the second type of jet fighter ever used in combat, a gun-slinging, plywood “wonder weapon” that helped to change the nature of aerial warfare forever.

Warren Gray is a retired, U.S. Air Force intelligence officer with experience in joint special operations and counterterrorism. He served in Europe, including with two fighter squadrons in Germany, and the Middle East, earned Air Force and Navy parachutist wings, four college degrees, and was a distinguished graduate of the Air Force Intelligence Operations Specialist Course, and the USAF Combat Targeting School. He is currently a published author and historian. You may visit his web site at: warrengray54.vistaprintdigital.com.