By: Randy Tucker

It was a great summer job at $9 an hour, with five hours of overtime each week.

Tuition cost only $260 a semester in those days, split rent of $100 each for a two-bedroom apartment, with another $75 for books, and we ate, drank, or hunted and fished with everything else.

The job itself was the most physical labor you can imagine, following a track hoe with a shovel and 12-pound digging bar (we called it dancing with the idiot stick) to keep the excavation for a gymnasium-sized underground water treatment plant on grade.

The grunt work went on for six weeks in the June and July heat of western Wyoming, but the paychecks were awesome.

After getting the entire 140 x 100 feet of the project to within a ¼” of grade, it was time to pour concrete. Most of those pours involved cement trucks backed up for a couple of hundred feet as we dumped wet concrete into 20 foot high forms.

That’s where Eddie Gonzalez comes into the picture.

We were working for Alder Construction, out of Salt Lake City. Loren Ricks, our superintendent on the project, would have been right at home with a whip 4,000 years ago driving the workers who built the pyramids. He was a stickler for detail, but he was fair, and the checks never bounced.

Loren had a reputation of only working with the best. Alex, our equipment operator, was a master behind the controls of the D-9 caterpillar and equally skilled on the 24-foot track hoe.

Frank Schmidt and I were the grunt laborers.

Eddie was a smooth operator, too, but in a different way. He was a flashy guy in his late 20s from Commerce City, Colorado.

Loren hired him to do the concrete finish work. He was a master with the trowel, wood float, and magnesium float. You could see your reflection in the wet concrete when Eddie shined it up on his final pass.

Flashy was the lifestyle Eddie lived. His pickup had more chrome on it than any vehicle I’d ever seen. Hubcaps, grills, bumpers, door handles, all the trim, every unpainted part of his flashy Ford pickup was gleaming with chrome.

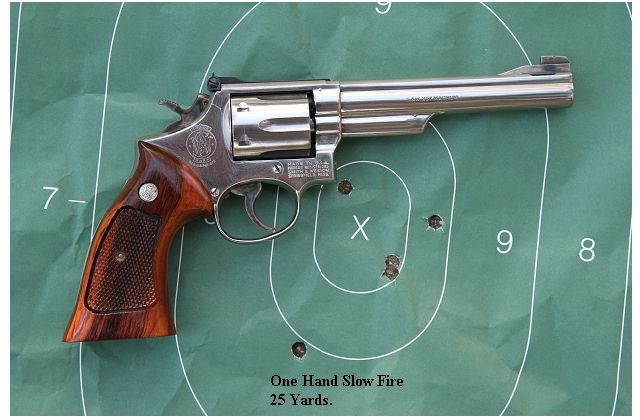

Eddie had another interesting piece of chrome with him — a Smith & Wesson .357 magnum revolver. It wasn’t really chrome, but instead had a bright nickel finish that Eddie always had polished. It reflected the sun like a mirror when he’d take it out of the front seat of his truck at lunchtime to show it off.

The Smith & Wesson was an older model, Eddie said it was a 1935 model, but I’m not sure; he never mentioned the year this one was made. It had the longest barrel I’d seen at the time on a Smith & Wesson revolver. Looking it up in later years, Smith & Wesson made the 1935 in barrel lengths up to 8 3/8 inches. This had to be one of those, but a nickel finish is rare.

We had an older carpenter on the job who was one of the most amazing craftsmen I’ve ever known. Leonard Romero could build anything out of wood. It was a pleasure when Loren assigned me to help Leonard with a project. Leonard was an old-school guy, not impressed by Eddie’s bravado at all.

Eddie was proud of that .357, routinely making outrageous claims on how accurate he was with it. One day his spiel almost cost him a week’s pay.

Eddie claimed he could hit a 30” target at 100 yards freehand with his Smith & Wesson. Leonard egged him on to prove it, and the challenge spread across the jobsite to include the city inspector and the concrete truck drivers.

One day, Eddie said he’d prove it to anyone who wanted to bet him with a week’s pay. To our surprise, Loren took the bet. Eddie did a little verbal shake and bake to bring the distance down to 75 yards.

After an early morning pour, we had everything cleaned up by 2 p.m., and the bet was on at quitting time three hours later.

The concrete crew came back, the inspector stayed over and brought a couple of guys from the city office with him to watch.

Frank and I set up a 55-gallon drum on edge at 75 yards from a mark north of the office trailer that faced a big hillside.

Eddie was making $13 an hour, so the bet was for $520.

With an audience of about 20 guys, Eddie took the .357 out of his truck.

A natural showman, he tossed a few blades of dry grass in the air to check the wind, he took a few one-handed practice aims, then moved to a two-handed grip for a few more trial runs.

He finally pulled the hammer back, set his feet, and carefully aimed the .357.

Eddie was nervous; we could see more sweat than the 95-degree heat should have produced running down his face.

No one in the crowd said anything.

Finally, a loud “boom,” the unmistakable sound of a .357 handgun at close distance bounced off the walls of the water treatment plant and echoed off into the distance.

There was a cloud of dust behind the 55-gallon drum, but the drum didn’t move.

Loren grinned, he’d just made 520 dollars.

“Not so fast, I know I hit it,” Eddie said. “Let’s go look at the barrel.”

We walked up to the barrel, but there was no mark on the front of it.

Loren grinned again, but Eddie said, “Look at the bottom.”

Sure enough, there was a hole the size of your finger near the rim on the backside of the drum.

Eddie had shot through the open bunghole from 75 yards away, and the bullet passed through the drum before punching a hole in the bottom. The dust we saw was from the dirt behind the barrel.

It was a great break from the drudgery of summertime construction work.

Loren paid up. It didn’t hurt him much, since we finished the job five weeks early the next summer, and he received a huge bonus for coming in so early on the schedule.

Randy Tucker is a retired history teacher and freelance writer from western Wyoming. He has a lifetime of experience in farming, ranching, hunting and fishing in the shadow of the Wind River Mountains. Contact him at [email protected].