By: Warren Gray

Copyright © 2023

“Every trooper has got to know the big picture, so that if he is

misdelivered…he can still exercise his individual initiative to

help accomplish the division’s mission.”

— “Combat Techniques,” Airlift Tactics magazine, 1986

On June 6, 2022, the 78th anniversary of the famous “D-Day” invasion of Normandy, France, during World War Two, the U.S. Army officially reactivated the 11th Airborne Division (“Arctic Angels”) at Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson, near Anchorage, Alaska. This is truly significant, because the U.S. currently has only two genuine, large-scale, airborne/paratrooper units, the fabled, 82nd Airborne Division (“All-American”) of World War Two fame, at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and the freshly-reactivated, 11th Airborne Division, which served in the Philippines during World War Two, now in Alaska. There is also the 173rd Airborne Brigade (“Sky Soldiers”) based in Vicenza, Italy, but it’s not division-strength.

During the course of my 21-year U.S. Air Force career, I served with the Joint Special Operations Command at Fort Bragg for two years, and graduated from the U.S. Navy’s jump school (which no longer exists) at Naval Air Station (NAS) Lakehurst, New Jersey, in 1986, becoming a special operations paratrooper for the course of that assignment. I didn’t make any combat jumps, but as soon as I went on active jump status, I read an interesting article in Airlift Tactics magazine, Volume IV, No. 4, Summer 1986, titled “82nd Airborne Division – Combat Techniques.”

Some things never change over time, and the Army’s combat jump tactics certainly fall into this category. The article states, “How We Do It in Combat…No safety wire on the right snap-connector of the reserve parachute…No belly band…The weapon will be jumped in the weapons case to protect it, but the M16 (or M4A1 carbine today) will be loaded. Do not chamber a round, though, until after you are on the ground…Light rucksacks only. Carry the bare minimum, which means water, ammo, food, razor, toothbrush, change of socks.

“Everybody jumps…No safeties…Every trooper is his own safety…If the DZ (Drop Zone) is under enemy attack when you land…Simply drop your weapons case, pop both capewells (the clips attaching the paratrooper’s jump harness to the parachute canopy), grab your weapon and rucksack, and start running. You can get rid of the harness later…Leaders will jump with their own radios…Speed is critical. The sooner we achieve our assault objectives, the better the odds for a successful mission.

“We will take care of injured jumpers later…Troopers must understand that they cannot stop on the DZ to help their buddies who were hurt on the jump. Speed is critical, and every trooper is needed to seize and secure assault objectives. This is a particularly important point to drive home to troops going into combat for the first time…If any item is critical to mission accomplishment, always take two-times the number you think you need…Go light on rations. A man can fight effectively for several days on just one C-ration (or MRE/Meal, Ready-to-Eat today) a day, but he can’t fight at all without water and ammo….speed, agility, and stamina are prerequisites to both mission accomplishment and reduced casualties. The basic load of ammo, plus water, plus extra ammo, makes for a tough enough load to begin with.”

In fact, if the jump altitude is low enough, no reserve chute is used. Combat parachute operations are so inherently risky that casualty rates of up to 75 percent (killed, wounded, injured, missing, or simply lost) are expected, with the mission carrying on, even with 75-percent losses, based upon actual, wartime experiences.

U.S. Army and Air Force members who complete a combat jump are authorized to wear a bronze, combat star on their silver jump wings, for each jump, as shown below:

Photo credit: bootsandchutes.com

The history of parachutes and paratroopers dates back to 1795, when Jean-Pierre Blanchard made the first true parachute jump from a balloon floating 3,000 feet above Paris, France, and broke his leg in a bad landing. In 1801, Blanchard made the first-ever parachute jump in the United States, with former President George Washington in attendance as a witness, and Blanchard again broke his leg. Even modern military parachutes descend much faster than depicted in Hollywood movies, at approximately 19 to 24 feet per second, or 14 to 16 miles per hour, so jump injuries are still quite common.

In World War One, parachutes were initially used by balloonists, military observers directing artillery fire, but by May 1918, soon after the combat death of the famous Red Baron, most German fighter pilots were wearing static-line parachutes. French, Italian, and Russian spies also used black parachutes to jump behind enemy lines at night. On October 17, 1918, Colonel William “Billy” Mitchell proposed that the 12,000 men of the 1st Infantry Division be made paratroopers and dropped behind German lines to attack Metz, France, from the rear, but his bold suggestion came too late in the war.

The U.S. Navy opened its own Naval Parachutist (NP-1) course at NAS Lakehurst, New Jersey, in 1928, which remained open until September 30, 1986, and from which this author graduated in May 1986. One of the great advantages of that school was that we each learned to pack our own chutes, so I never had even the slightest malfunction upon jumping. I cannot say the same for Army parachute-packing practices, however. Also in 1928, the Italians formed the first true paratrooper company, using British parachutes.

The following year, the Russians formed a paratrooper battalion, also using British Irvin chutes, and then a military test parachute unit in 1931. In the early 1930s, they invented sport parachuting, and in 1933, Russian paratroopers made the world’s first mass tactical jump over Kiev (now Kyiv), Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, using freefall Irvin parachutes with automatic opening devices (AODs).

The United States remained well behind the power curve as France opened a military jump school in 1935, and the Russians made another mass tactical jump near Moscow, with 5,200 paratroopers! Germany opened a jump school at Stendal in 1936, followed closely by the Italians in 1938, and in October of that year, German Colonel Kurt Student formed the 7th Parachute Division for the invasion of Czechoslovakia, but they were never used, and were soon disbanded. Student reformed the division in 1939 as a general, and the first combat action by paratroopers took place on November 30th, with Russian paratroopers jumping into Petsamo, Finland, during the Winter War.

World War Two saw the massive employment of paratroopers by the Allies and Axis powers alike, beginning with German parachute assaults on Norway in April and May 1940, meeting only light resistance, then the German 7th Parachute Division jumped into Rotterdam, the Netherlands, with 4,500 men, and seized the city in May. The British opened their own jump school at RAF Ringway in June 1940, with Prime Minister Winston Churchill calling for a formation of 5,000 paratroopers, and the first were from 2 Commando, which later became 11 Special Air Service (SAS) Battalion, and then 1 Parachute Battalion.

The Brits then made seven jumps over 12 days to earn their wings, including two from a silent, tethered, Lindstrand parachute-training balloon at 700 to 800 feet altitude, with no reserve chutes in use until 1956. Since the late 1990s, they no longer use balloons, currently require only four jumps (three in daylight, plus one at night) to qualify at RAF Brize-Norton, and now routinely jump from C-130J Hercules (retired by June 30, 2023), C-17A Globemaster III, or Airbus A400M Atlas C.1 fixed-wing transports at 600 to 1,000 feet altitude, with equipment. This is very low by U.S. standards, but British parachutes open much faster.

The U.S. Army created a parachute test platoon at Fort Benning, Georgia, in June 1940, and began paratrooper recruiting in November, with a weight limit of 185 pounds per soldier. (The more you weigh, the harder you hit the ground, even under a parachute canopy.) Meanwhile, the U.S. Marine Corps’ 1st Parachute Battalion began jump training at Lakehurst in October. In April 1941, the U.S. Army jump school opened at Fort Benning (now Fort Moore), where it still remains today. The next month, the German 7th Parachute Division jumped into Crete, sustaining 56-percent casualties, but winning the invasion, and setting the precedent for an expectation of very high paratrooper casualties in the future.

The first real, Allied paratrooper assault success was Operation Biting, the British raid on a German, Würzburg radar station at Bruneval (Normandy region), France, on the night of February 27 to 28, 1942, by C Company, 2nd Parachute Battalion under Major John Frost. They were to locate the Würzburg radar set, photograph it, and dismantle part of it for transportation back to England. The attack was brilliantly successful, especially as a morale booster for the British public, and Frost was awarded the Military Cross, with one participant, Commander F.N. Cook of the Royal Australian Navy, earning the prestigious Distinguished Service Cross, for “exemplary gallantry during active operations against the enemy at sea,” for leading the assault force evacuation under intense, hostile fire.

U.S. Army combat jumps by the newly-formed (March 1942), 82nd Airborne Division began on November 8, 1942, in Algeria, during the Allied invasion of North Africa, and they made two more mass jumps into Algeria and Tunisia in November and December 1942. In 1943, American soldiers jumped into Italy five times at night, suffering stunning, 83-percent casualties in one instance, and there was a daylight, combat jump into New Guinea at ultra-low altitude, as well.

America’s most famous combat jumps were the two mass tactical operations in the early morning hours of June 6, 1944, over Normandy, France, by the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions, in support of the D-Day invasion, dropping more than 13,000 paratroopers at night. Afterward, there were six more U.S. combat jumps in 1944, and five in 1945. American paratroopers made six combat jumps during the Korean War, and five in the Vietnam War, plus six more that were formerly classified, and 13 more small-team insertions that resulted in 10 American Medals of Honor for Special Forces men.

Subsequently, there were three U.S. combat jumps into Grenada in 1983, two into Panama in 1989 (from 500 feet altitude, with no reserve chutes), two in Iraq in 1991, three into Afghanistan in 2001 and 2003, four more into Iraq in 2003, and Army Ranger combat jumps into Afghanistan in 2004 and 2009.

These figures naturally do not include ultra-secret combat jumps made by OSS (Office of Strategic Services) military operatives in World War Two, or by CIA paramilitary operatives since then. Some of the most daring and secretive combat jumps in history were made by OSS agents into occupied France or Germany, from modified, camouflaged, B-24D/H/J Liberator bombers or all-black, A-26C Invader bombers of the 801st Bombardment Group (“Carpetbaggers,”) later renamed the 492nd Bombardment Group) or 856th Bombardment Squadron at just 250 to 350 feet altitude, all at night, using British parachutes. They successfully delivered more than 1,000 secret-agent parachutists behind enemy lines during the latter part of the war.

MC-6 (Maneuverable Canopy-6) parachute. Photo credit: U.S. Army

Currently, the U.S. Armed Forces utilize two primary types of parachutes, the non-steerable T-11, as shown in the lead photo at the beginning of this article, for mass tactical operations by the 11th and 82nd Airborne Divisions, and the MC-6 steerable, round chute for special operations teams and other small-unit assaults. These are both improvements over the previous T-10D and MC1-1B models, allowing for slightly reduced rates of descent to prevent jump injuries. Highly-maneuverable MC-4 (Army) and MC-5 (Marines) military freefall, ram-air, parabolic chutes are used primarily by special operations forces for pinpoint landings, replacing older, MT-1X parachutes.

Most peacetime, static-line, training jumps are made from 1,500 feet, some from 1,250 feet, and rarely from 800 feet, since U.S. parachutes require at least 350 to 450 feet to fully open, even in combat. Upon exiting the aircraft, a paratrooper will typically fall 240 to 370 or more feet in the four to five seconds before the canopy opens, so combat jumps normally take place from 500 to 800 feet altitude, to allow for a small margin of safety.

British military parachutes, however, from the Irvin GQ X-Type Mk. 2 of World War Two to the modern, Irvin GQ LLP Mk. 1, with H124 canopy, have been designed to open canopy-first, very quickly, from jump altitudes as low as 250 feet, so other nations sometimes have better parachute technology. The U.S. Army would like to have a parachute for use at 250 feet and 150 knots airspeed, with a descent rate of 17 feet per second, but even the British LLP chute is rated for 140 knots (150 knots absolute maximum) and 18.5 fps, so the desired standards have not yet been fully achieved.

Some military parachute variants, such as the older MC1-1C, incorporate low-porosity (nicknamed “No-Porosity” or “NoPo”), nylon canopies for a slower, safer rate of descent, but the tradeoff is a harder opening shock, so these models are in the minority of available chutes. But I certainly appreciated a softer, NoPo landing whenever I could get one! The standard Airborne saying is that, “Any jump you can walk away from is a good one,” and NoPo chutes definitely reduce jump injuries.

The maximum safe exit speed for U.S. paratroopers is 125 knots (144 mph), but I have semi-safely jumped at 140 knots (161 mph) airspeed, with a violent, bone-jarring, opening shock, so combat jumps may be accomplished at slightly higher speeds to achieve a quick opening at very low altitude. In peacetime, the safety limit for ground wind speed is 13 knots (15 mph), but in wartime, that’s nearly doubled, to 25 knots (29 mph.).

U.S. Army paratroopers wear the standard Operational Camouflage Pattern (OCP) uniform in the field, with maroon paratrooper’s beret (since 1980, inspired by the British “Paras” in World War Two) worn in garrison. Issued weapons include the Colt M4A1 carbine in 5.56mm NATO, and SIG M17 (or M18) service pistol in 9x19mm. The most-common knife is the standard, M9 Phrobis III bayonet, although many paratroopers purchase their own combat knives from commercial sources.

U.S. Army paratrooper in Italy, wearing OCP uniform, with Colt M4A1 carbine and SIG M17 pistol. Photo credit: U.S. Army

Why would any nation maintain such a large, active, paratrooper force in these modern times of very few airborne assaults in actual combat? According to noted author and U.S. Special Forces veteran Gordon L. Rottman, “The concept of building esprit de corps by ‘rites of passage’…for the purpose of unit cohesion, instilling aggressiveness, and enhancing unit prestige, (is) lost on many conventionally-minded soldiers…But it is another matter to voluntarily and frequently throw oneself, with all sorts of paraphernalia strapped on, out of a perfectly good aircraft, in full knowledge of the risk of injury or even death…(and) riding in a helicopter into a potentially ‘hot’ landing zone on active service is little different emotionally from waiting to make that vigorous exit over a Fort Bragg drop zone.

“This pre-exposure to coping with combat stress and the control of fear makes parachute training well worth the effort in the interests of maintaining a peacetime, immediate-action force capable of swift transition…to the realities of combat half a world away, in a totally different climate…It is for these reasons that many nations maintain a parachute force, not because it is their principal means of delivery…They want troops who can face challenging odds with speed and flexibility, and sub-units capable of independent operations.”

Major General Aubrey S. “Red” Newman, former commander of the 34th Infantry Regiment in World War Two, and holder of the Distinguished Service Cross, the Army’s second-highest award for valor, added that, “Parachute jumping tests and hardens a soldier under stress in a way that nothing short of battle can do. You never know about the others. But paratroopers will fight. You can bet on that.”

One of the most successful paratrooper raids in history was the incredible combat mission into Congo-Léopoldville by Belgian Special Forces on November 24, 1964 (See my previous Gunpowder Magazine article on “‘Red Dragon’: Guns of the Belgian Special Forces” from April 18, 2022). Five U.S. Air Force C-130E Hercules transports dropped 320 elite, Belgian Para-Commandos from 700 feet within a matter of seconds, in a daring assault named Operation Dragon Rouge (“Red Dragon”) in French.

Fighting against an estimated 600 Simba insurgents in the area, the Belgians secured the airfield and cleared the blocked runway within 40 minutes, permitting seven more C-130s to land, before moving into the nearby city. The operation was a resounding success, with hundreds of Simba warriors killed, for the loss of only two Belgians killed and 12 wounded, and they swiftly rescued 1,650 European hostages and 150 Congolese civilians on the first day alone, and then about 350 more people the next day.

In conclusion, combat jump tactics may differ significantly from peacetime training procedures, considering the need for speed, surprise, agility, and flexibility in accomplishing mission objectives, and with the grim realization that casualties in any paratrooper assault may be very high. With the recent reactivation of the 11th Airborne Division in 2022, the U.S. Army is very clearly preparing for future conflicts that may require large-scale, airborne assaults.

* * *

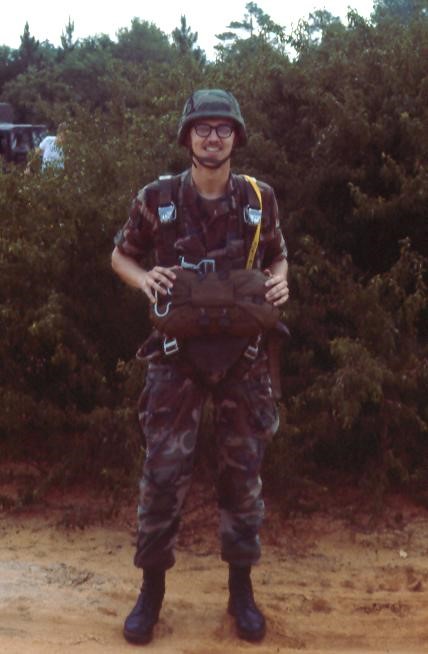

Author parachuting at Fort Bragg, NC, with MC1-1C “NoPo” parachute, in 1987. Photo credits: Melody Gray

Warren Gray is a retired, U.S. Air Force intelligence officer with experience in joint special operations (as a paratrooper) and counterterrorism. He served in Europe and the Middle East, earned Air Force and Navy parachutist wings, four college degrees, and was a distinguished graduate of the Air Force Intelligence Operations Specialist Course, and the USAF Combat Targeting School. He is currently a published author, historian, and hunter. You may view his website at: warrengray54.com