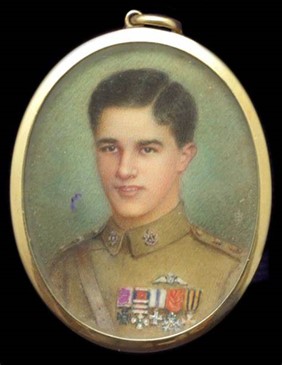

Captain Georges Guynemer (French) Photo credit: Museum of the Legion of Honor

By: Warren Gray

Copyright © 2023

“Fly on and fight on to the last drop of blood and the last drop of fuel,

to the last beat of the heart…Death may be right on my neck…Higher

authority has suggested I should quit flying before it catches up with

me…‘It is stupid, after all, to die so unnecessarily a hero’s death.’”

— Captain Manfred von Richthofen, the “Red Baron,” 1917

I’ve previously written articles for Gunpowder Magazine on the great, American, ace pilot Frank Luke, Jr., and the death of Germany’s leading WWI ace, Manfred von Richthofen, the “Red Baron” (See “Guns of the Red Baron’s Last Flight,” from April 18, 2020, and “American Hero: Frank Luke, Jr., ‘Balloon Buster,’” from March 1, 2023). Both were unfortunately killed in action at the height of their successes by hostile ground fire, something that fighter pilots engaged in air-to-air combat often ignore, at their own peril.

Today, we’ll address the final flights of famous British and French fighter aces Captain Albert Ball and Captain Georges Guynemer, both of whom mysteriously disappeared in blazing combat, and were initially listed as missing in action, until additional details of their deaths could be obtained from eyewitnesses.

Captain Albert Ball, Photo credit: Wikipedia

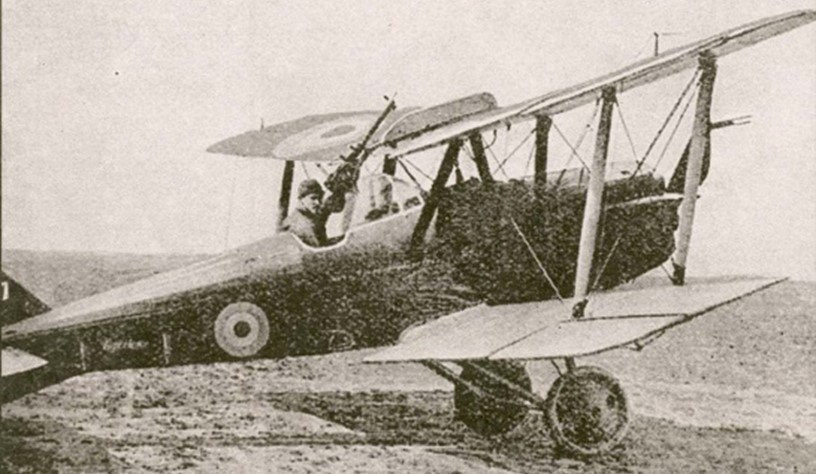

Captain Albert Ball’s red-nosed, S.E. 5A fighter. Photo credit: miniatures-lyon.com

At the very young age of 20, Albert Ball held the temporary rank of captain, as a flight commander of elite, handpicked pilots in No. 56 Squadron, Royal Flying Corps (RFC.) By early May of 1917, he had shot down 43 German aircraft and one observation balloon confirmed in just over one year, with 25 more unconfirmed victories, and was Britain’s highest-scoring ace (an “ace” has five or more kills), the first to become an instantly recognized national hero.

He had already earned the Military Cross (MC) for shooting down a German military balloon in 1916, and the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) with two Bars (three separate awards) “for conspicuous skill and gallantry,” for attacking and downing multiple enemy aircraft, frequently at a point-blank range of just 10 to 15 yards, often while seriously outnumbered in the air.

Ball became famous for his solo “lone-wolf” tactics, usually flying alone, and carefully maneuvering himself below and behind unsuspecting German fighters or observation aircraft, and opening fire with the Lewis machine gun on a flexible, J-shaped, Foster mount atop the upper wing of his fighter. This was his preferred weapon.

As a great ace, he was permitted to fly two different aircraft into battle, the light, nimble, French-made Nieuport 17 for lone-wolf missions, and the heavier, more stable, less-responsive, British S.E. 5A (Scout, Experimental, 5A) while flying with his squadron mates. He didn’t really like the S.E. 5A though, partly because of constant problems with the single Vickers machine gun on the engine cowling jamming, and additional problems with its synchronizer gear for firing through the propeller arc. It was a notoriously unreliable combination on the S.E. 5A, still causing trouble for him to the very end.

Captain Albert Ball in S.E. 5A fighter, holding his preferred Lewis gun. Photo credit: vlib.us

So, Ball clearly preferred the flexibly mounted Lewis machine gun on the upper wing, which hardly ever jammed, and required no synchronizer gear. His S.E. 5A was modified with the addition of a longer-range fuel tank, and a cockpit holster for his Colt M1911 (American) service pistol. According to fellow ace James McCudden, “It was quite a work of art to pull this gun down and shoot upwards, and at the same time manage one’s machine accurately.” Ball would sometimes stand up to reload the gun, holding the control stick between his knees, a true daredevil.

Indeed, Ball preferred to fly without a helmet or goggles, feeling the rushing wind in his hair, and had earned the nickname of the “Berserker,” after the fabled Viking warriors who fought in a trance.

On the evening of May 6, 1917, Albert flew the Nieuport 17 again while the synchronizer gear of his problematic S.E. 5A was in for repair, and he destroyed a German Albatros D.III fighter, scoring his 44th and final aerial kill. That same night, in his last letter to his father, Ball wrote that, “I do get tired of always living to kill, and am really beginning to feel like a murderer. Shall be so pleased when I have finished.”

The very next evening, May 7, 1917, Albert Ball flew his red-nosed S.E. 5A again, leading 11 British fighters into action near Douai, France, against five German Albatros D.III fighters from Jasta 11, the fabled, Red Baron’s own unit, including the baron’s younger brother, Lothar von Richthofen, an air ace in his own right, with 19 confirmed kills at that time. A violent dogfight ensued, with Ball chasing von Richthofen’s red Albatros near Annœullin, in far, northern France, as visibility rapidly decreased beneath thunderclouds near 8 PM.

“The Last Fight of Captain Ball,” by Norman Arnold, 1919. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Lothar survived the attack, and later wrote that, “My machine was damaged (punctured fuel tank), and I landed with a dead prop, near the hostile machine.” This clearly indicates that he saw a British S.E. 5A hit the ground. Ball had disappeared into the clouds, and no other aircraft had crashed in the vicinity that day, so von Richthofen obviously landed after the British fighter crashed. Albert Ball was officially listed as missing in action.

On the ground, German brothers Franz and Carl Hailer and the other two men in their party were from an aerial reconnaissance unit, Flieger-Abteilung A292, and they all saw an S.E. 5A falling rapidly from the clouds at only 200 feet altitude, in an inverted, flat spin, with the propeller shut down. Franz wrote that, “It was leaving a cloud of black smoke…caused by oil leaking into the cylinders.”

In fact, the troublesome, Hispano-Suiza 8b V-8 engine on the British fighter engine was known to flood its intake manifold with fuel when upside down, and then stop running. It was also plagued with serious gear-reduction system problems. Hailer and his companions watched it pass low over a line of trees and crash into the ground. They immediately rushed to the crash site and found the dead body of Captain Albert Ball in the wreckage, with a broken back, broken arm, and crushed chest. There were no bullet holes or other battle damage to the aircraft. Ball was subsequently buried with full military honors in the local cemetery at Annœullin, where his body still rests today.

The Germans credited Lothar von Richthofen with shooting down Ball, but he disputed this, claiming that he shot down a Sopwith Triplane, not an S.E. 5A. Actually, the Sopwith pilot returned home unscathed. But Germany needed a propaganda victory, and Ball’s accidental death neatly provided that. Most likely, Albert Ball became disoriented inside the low thundercloud and suffered temporary vertigo, inverting his aircraft, which resulted in the unreliable engine shutting down. Allied pilots did not wear parachutes at that phase of the war, and in any event, it would have been virtually impossible to bail out of a fighter in an inverted, flat spin.

Ball was officially listed as missing in action for the next three weeks, with his squadron mates hopeful that he’d perhaps been captured alive and was a prisoner of war, but all hopes were dashed when the Germans dropped notes confirming his demise.

After his death, Albert Ball was promoted to the permanent rank of captain and was awarded the Cross of a Knight of the Legion of Honor by the French government, the Victoria Cross, Britain’s highest decoration for valor in combat, and the Russian Order of Saint George. His Victoria Cross citation reads, in part, “For most conspicuous and consistent bravery from the 25th of April to the 6th of May, 1917…Captain Ball, flying alone…destroyed forty-three German aeroplanes and one balloon, and has always displayed most exceptional courage, determination, and skill.”

Captain Georges Guynemer. Photo credit: leparisien.fr

Captain Georges Guynemer with his SPAD S.XIII fighter. Photo credit: forum.treefrogtreasures.com

Our next heroic ace was Georges Guynemer, age 22, of the French Air Service, a young captain in command of Escadrille N.3 (“Storks”), who achieved 54 confirmed aerial kills, as France’s second highest-scoring ace, and an exalted, national hero. Like Ball, Guynemer was shy and introspective, and was embarrassed by all of the publicity surrounding his wartime exploits. He had earned the French Legion of Honor, the War Cross with 26 palms, Military Medal, British Distinguished Service Order, and Serbian Order of Karađorđe’s Star with swords, among other notable awards.

Guynemer was influential enough to affect French fighter design, writing in December 1916 to the SPAD (Société Pour l’Aviation et ses Dérivés, or “Society for Aviation and its Derivatives”) chief designer that the SPAD S.VII fighter was inferior to the German Halberstadt aircraft: “The 150-HP SPAD is not a match for the Halberstadt. Although the Halberstadt is probably no faster, it climbs better, consequently it has the overall advantage. More speed is needed; possibly the airscrew could be improved.”

As a direct result, SPAD developed two new models, the SPAD S.XII, built in small numbers, and SPAD S.XIII, more widely produced. Guynemer’s original SPAD S.VII is preserved and displayed at the French Air and Space Museum. He used it as the first Allied pilot to shoot down a German Gotha G.III heavy bomber on February 8, 1917, his 31st aerial victory, and in May 1917, his highest-scoring month, when Ball was killed, Guynemer downed seven German aircraft, including a quadruple credit on May 25th.

By July 1917, Georges was flying the new SPAD S.XII, armed with one Vickers machine gun, and a Puteaux 37mm SAMC (Semi-Automatic Motor Cannon) cannon firing through the propeller shaft. It was a real beast to fly, because the cannon’s rearwards-protruding breech required separate aileron and elevator controls, split from each other on opposing sides of the cockpit. The big, single-shot cannon had to also be manually reloaded in flight, with a substantial recoil when fired, and filled the canopy with fumes after every shot. Only 12 rounds were carried in the cockpit. However, Guynemer called it his “Magic Aircraft,” and used it with dramatic effect, bringing down two German fighters on July 27 and 28, and thereby attaining his 50th confirmed kill!

His final flight took place on the morning of Tuesday, September 11, 1917, near Langemark-Poelkapelle, in western Belgium, 10 miles from the French border, when he took off at 8:30 AM with novice pilot Second Lieutenant Jean Bozon-Verduraz, with both men flying SPAD S.XIII fighters. This was a newer aircraft, without the hefty, 37mm cannon, and with twin Vickers .303-caliber machine guns on the engine cowling instead.

At 9:25 AM, near Poelkapelle, Guynemer sighted a lone Rumpler C.IV observation plane and dove toward it from 12,000-feet altitude. Bozon-Verduraz saw eight Fokker E.III monoplanes above him, and by the time he had shaken them off, his leader was nowhere in sight, so he flew home alone, and Guynemer never returned. He was officially listed as missing in action two weeks later.

The French War Department released this statement on September 25, 1917: “Guynemer sighted five machines of the Albatros type D.III. Without hesitation, he bore down on them. At that moment, enemy patrolling machines, soaring at a great height, appeared suddenly and fell upon Guynemer. There were 40 enemy machines in the air at this time, including Baron von Richthofen and his circus division of machines, painted in diagonal, blue-and-white stripes.

“Toward Guynemer’s right, some Belgian machines hove in sight, but it was too late. Guynemer must have been hit. His machine dropped gently toward the Earth…the machine was not on fire.” German Second Lieutenant Kurt Wissemann, age 24, an Albatros D.V pilot of Jasta 3, was credited with shooting down Guynemer, thus scoring his own fifth kill and briefly becoming an ace, but Wissemann was killed in action a little more than two weeks later, on September 28, 1917, over Westrozebeke, Belgium.

But reports indicate that the SPAD was already falling when Wissemann fired upon it, so it seems more likely that Guynemer, who suffered from combat fatigue and needed a rest, was probably exhausted and a bit careless, and was hit by the machine gun of the Rumpler’s observer, Reserve Second Lieutenant Max Psaar. Unfortunately, Psaar and his pilot, Georg Siebert, were both shot down by Belgian Second Lieutenant Maurice Medaets, a SPAD S.VII pilot, and killed in action three hours later, near Diksmuide, so they did not survive long enough to make a claim for shooting down Guynemer. Such are the mysterious fortunes of war, proving that truth is, indeed, stranger than fiction.

An American Red Cross communiqué confirmed the grim details: “Guynemer was shot through the head north of Poelkapelle, on the Ypres front. His body was identified by a photograph on his pilot’s license found in his pocket. The burial took place at Brussels in the presence of a guard of honor, composed of the 5th Prussian Division…The burial was about to take place at Poelkapelle, when the bombardment preceding the British attack at Ypres started. The burying party hastily withdrew, taking the body with them…was given all possible military honors.”

Georges Guynemer’s death came as a profound shock to the French people, but his shining example continued to inspire the French toward ultimate victory. Guynemer had once bluntly stated that, “Until one has given all, one has given nothing.” Guynemer was a daring and aggressive fighter pilot, but ultimately, his incredible luck finally ran out.

He was a revered, national hero, but even great heroes are flesh and blood. As President John F. Kennedy stated in a speech on June 10, 1963, “We all inhabit this small planet. We all breathe the same air…And we are all mortal.” So it was with the untimely deaths of famous air aces Albert Ball and Georges Guynemer in the Great War.

* * *

Author after his 1929 Waco biplane flight, June 10, 2023. Photo credit: Melody Gray

Warren Gray is a retired U.S. Air Force intelligence officer with experience in joint special operations and counterterrorism. He served with three fighter squadrons in Europe (traveled to France) and the Middle East (two F-4E Phantom II squadrons in Germany, and one F-117A Nighthawk stealth fighter squadron in Saudi Arabia), earned Air Force and Navy parachutist wings, and four college degrees, including a Master of Aeronautical Science degree, and was a distinguished graduate of the Air Force Intelligence Operations Specialist Course, and the USAF Combat Targeting School. He is currently a published author and historian.